Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

Diabetic retinopathy, the leading cause of blindness in working-age Americans, is characterised by reduced neurotrophic support and increased proinflammatory cytokines, resulting in neurotoxicity and vascular permeability. We sought to elucidate how oxidative stress impairs homeostasis of nerve growth factor (NGF) and its precursor, proform of NGF (proNGF), to cause neurovascular dysfunction in the eye of diabetic patients.

Methods

Levels of NGF and proNGF were examined in samples from human patients, from retinal Müller glial cell line culture cells and from streptozotocin-induced diabetic animals treated with and without atorvastatin (10 mg/kg daily, per os) or 5,10,15,20-tetrakis (4-sulfonatophenyl)porphyrinato iron (III) chloride (FeTPPs) (15 mg/kg daily, i.p.) for 4 weeks. Neuronal death and vascular permeability were assessed by TUNEL and extravasation of BSA-fluorescein.

Results

Diabetes-induced peroxynitrite formation impaired production and activity of matrix metalloproteinase-7 (MMP-7), which cleaves proNGF extracellularly, leading to accumulation of proNGF and reducing NGF in samples from diabetic retinopathy patients and experimental models. Treatment of diabetic animals with atorvastatin exerted similar protective effects that blocked peroxynitrite using FeTPPs, restoring activity of MMP-7 and hence the balance between proNGF and NGF. These effects were associated with preservation of blood–retinal barrier integrity, preventing neuronal cell death and blocking activation of RhoA and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38MAPK) in experimental and human samples.

Conclusions/interpretation

Oxidative stress plays an unrecognised role in causing accumulation of proNGF, which can activate a common pathway, RhoA/p38MAPK, to mediate neurovascular injury. Oral statin therapy shows promise for treatment of diabetic retinopathy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diabetes disturbs retinal homeostasis by activating glial cells, reducing neurotrophic support and increasing proinflammatory cytokines. These changes lead to accelerated cell death within the inner retinal and ganglion cells [1–3] and blood–retinal barrier (BRB) breakdown resulting in macular oedema and neovascularisation [4]. Clinically, the disease manifests as diabetic retinopathy and eventually leads to impaired vision. The gold standard for treating diabetic retinopathy is limited to laser photocoagulation, an invasive procedure with serious side effects, as reviewed by Ali and El-Remessy [5]. The lack of approved pharmacological treatment for diabetic retinopathy makes it essential to identify effective therapeutic approaches. Thus, understanding the molecular mechanisms that regulate retinal neurovascular dysfunction is of major clinical importance.

Traditionally, neurotrophins such as nerve growth factor (NGF) promote cell survival. However, we and others have reported paradoxical increases in levels of NGF despite neuronal death in clinical and experimental diabetic retinopathy [1, 6, 7]. Our recent study described a mechanism of peroxynitrite-induced impairment of NGF signal via tyrosine nitration of tyrosine receptor kinase A (TrkA), the NGF survival receptor, and upregulation of p75NTR (NTR is also known as NGFR), the neurotrophin receptor, causing retinal neurodegeneration in clinical and experimental diabetes [1]. These findings prompted us to study the role of peroxynitrite in regulating release of NGF in diabetic humans and to elucidate how it induces neurodegeneration and BRB breakdown in experimental models. NGF is synthesised and secreted by glia as a precursor proform of NGF (proNGF), which is proteolytically cleaved, intracellularly by furin and extracellulary by the matrix metalloproteinase-7 (MMP-7), to generate the mature form (NGF) [8]. Under oxidative stress and inflammatory conditions, the activity of proteases is altered, possibly resulting in accumulation of proNGF in injured neuronal and vascular tissue [9]. However, little is known about the production pattern and activity of MMP-7, and the resulting imbalance between NGF and proNGF under diabetic conditions.

The molecular link between two well-documented early hallmarks of diabetic retinopathy, i.e. accelerated neuronal death and vascular permeability, remains obscure [1–3, 10–13]. While proinflammatory cytokines are known to activate Rho family kinases leading to actin cytoskeleton rearrangement and cell permeability in vasculature, Rho family members are also essential regulators of neuronal survival in the nervous system, as reviewed by Linseman and Loucks [14]. Therefore, we examined the role of RhoA activation and its downstream target, p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38MAPK), as well as the protective actions of atorvastatin, an inhibitor of the rate-limiting enzyme of cholesterol synthesis and activation of the Rho family GTPases. In the present study, we demonstrate how accumulation of proNGF and subsequent activation of RhoA and p38MAPK may play a central role in mediating diabetes-induced neurovascular injury. We also describe the molecular mechanisms by which blocking of diabetes-induced peroxynitrite formation in the diabetic retina exerts protective effects, such as (1) restoration of MMP-7 levels and activity, and thus of the balance between proNGF and NGF, and (2) preventing activation of RhoA and p38MAPK.

Methods

Human samples

Human specimens were obtained with Institutional Review Board approval from the human assurance committee at the Medical College of Georgia and the Veteran Affairs Medical Center.

Aqueous humour samples were collected from the Medical College of Georgia Eye Clinic from patients undergoing intravitreal injections and were identified by ophthalmologist J. J. Nussbaum as being from patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) and more than 25 years of diabetes duration, or from non-diabetic controls (Table 1). Aqueous humour (100 μl) was collected and kept refrigerated for further analyses.

Post mortem vitreous and retinal samples were obtained from the GA Eye Bank. Samples were identified as being from diabetic (more than 10 years of disease duration) or non-diabetic controls. Human vitreous samples were kept refrigerated and retinas were snap-frozen for further analyses. Demographics and retinal pathology of post mortem samples were recently published by our group [1].

Animal preparation

Procedures with animals were performed in accordance with the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology (ARVO) and the Veterans’ Affairs Medical Center Animal Care and Use Committee. Three sets (totalling 67 animals) of male Sprague–Dawley rats (∼250 g, 6 weeks old) from Harlan Laboratories (Indianapolis, IN, USA) were randomly assigned to control, treated control, diabetic or treated diabetic groups. Diabetes was induced by intravenous injection of streptozotocin (60 mg/kg). Detection of glucose in urine and blood glucose levels >13.9 mmol/l indicated diabetes. Treatment was initiated the day after confirmation of diabetic status and continued for 4 weeks for various endpoints. Groups treated with atorvastatin (Pfizer, NY, USA) received the drug by oral gavage (per os [p.o.]) at 10 mg/kg daily. Additional groups received (i.p.) the peroxynitrite decomposition catalyst 5,10,15, 20-tetrakis (4-sulfonatophenyl)porphyrinato iron (III) chloride (FeTPPs) (15 mg/kg daily or vehicle) and served as controls. Streptozotocin-injected animals had significant increases of blood glucose level (27.2 mmol/l) compared with controls (9.2 mmol/l). Treatment with atorvastatin had no effect on body weight or blood glucose levels in diabetic rats (27.3 mmol/l) or in treated controls (9.1 mmol/l). As shown before, treatment with FeTPPs had no effect on body weight or blood glucose levels in diabetic rats [1].

Tissue culture

Transformed retinal Müller glial cell line culture cells (rMC-1) (V. Sarthy, Department of Ophthalmology, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, USA) were previously characterised to express Müller cell markers [15]. Cells were maintained in high glucose (25 mmol/l) or normal glucose (5 mmol/l) for 72 h or treated with 100 μmol/l peroxynitrite overnight (16 h). Medium for rMC-1 was DMEMF12 with 10% (vol./vol.) FBS and penicillin/streptomycin. Peroxynitrite stocks were prepared in 0.1 mmol/l NaOH (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). An equal amount of vehicle or decomposed peroxynitrite was used for control experiments.

Retinal protein extraction and western blot

Retinas were homogenised in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer to examine the abundance of various proteins as described by our group [1]. Purchased antibodies included: proNGF and NGF (Alomone Labs, Jerusalem, Israel); p75NTR (Millipore); MMP-7 (AnaSpec, Fremont, CA, USA); and phospho-p38MAPK and p38MAPK (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA). Membranes were reprobed with β-actin (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) to confirm equal loading. Primary antibody was detected by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated sheep anti-rabbit antibody and enhanced-chemiluminescence (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA). The band intensity was quantified using densitometry software (Alpha Innotech, CA, USA) and expressed as relative optical density.

Immuno-colocalisation of proNGF in Müller cells

Fixed retinal optimal cutting temperature compound frozen sections were reacted with anti-proNGF antibody (Alomone Labs) and anti-cellular retinaldehyde-binding protein (CRALBP) for Müller cells (Affinity BioReagents, Rockford, IL, USA). Activation of Müller cells was assessed by immunostaining of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) (Affinity BioReagents). Images were collected using confocal microscopy (Zeiss, Jena, Germany).

Oxidative and nitrative markers

Slot-blot analysis was performed as described previously [1, 16]. Retinal homogenate was immobilised on to a nitrocellulose membrane that was reacted with antibodies against 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (4-HNE) (Alpha Diagnostics, San Antonio, TX, USA) or nitrotyrosine (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA, USA), and optical density of samples was compared with controls.

Rho kinase activity

Rho kinase activity was assessed by pull-down assay. As previously described, retinas were homogenised in assay buffer [17]. Bound Rho proteins were detected by western blot using anti-RhoA antibody (Millipore).

MMP-7 activity

MMP-7 activity was determined in human aqueous humour samples or culture medum using fluorescent-labelled substrate (AnaSpec). Results were compared with a standard concentration of MMP-7 after activation of the enzyme by adding aminophenyl mercuric acetate (Sigma) for 1 h, followed by fluorescent substrate. Then MMP-7 activity was measured fluorimetrically with a plate reader (excitation 370 nm, emission 460 nm) (BioTek).

Blood–retinal barrier function

Integrity of the BRB was measured as previously described by our group [3, 12]. Plasma was assayed for fluoresciene concentration using a plate reader (excitation 370 nm, emission 460 nm) (BioTek). A standard curve was established using BSA-fluorescence in normal rat serum. Through serial sectioning (10 μm) and imaging (200 μm2) of retinal non-vascular areas, extravasation of BSA-fluorescence was detected.

Neuronal cell death

TUNEL assay was performed using immunoperoxidase staining (ApopTag-peroxidase) in whole-mounted retinas or ApopTaG in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound-frozen sections as described previously by our group [1]. The total number of TUNEL horseradish peroxidase-positive cells was counted using light microscopy.

Data analysis

The results are expressed as means ± SEM. Differences among experimental groups were evaluated by ANOVA and the significance of differences between groups was assessed by the post hoc test (Fisher’s protected least significant difference) when indicated. Significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Results

Diabetes causes imbalance of proNGF and NGF in experimental and human samples

Studies in aqueous humour samples from patients diagnosed with PDR showed significant accumulation of proNGF (∼fivefold) and 65% reduction in NGF compared with non-diabetic patients (Fig. 1a, b). A similar pattern was observed, though to a lesser extent, in human vitreous samples from patients with >10 years diabetes duration, namely ∼threefold accumulation of proNGF and 35% reduction in NGF compared with non-diabetic patients (Fig. 1a, b). In parallel, levels of proNGF in 4-week-old diabetic rats (equivalent to 5 years of human diabetes) showed a twofold increase that was associated with 50% reduction in mature NGF compared with controls. Treatment of diabetic animals with the peroxynitrite decomposition catalyst, FeTPPs (15 mg/kg daily, i.p.), or atorvastatin (10 mg/kg daily, p.o.) for 4 weeks restored the balance between NGF and proNGF to normal levels (Fig. 1c, d).

Diabetes causes imbalance of proNGF and NGF in experimental and human samples. a Representative western blot showing significant accumulation of proNGF (32 kDa) levels (∼threefold) in human (H.) diabetic vitreous samples (DR) and (fivefold) in human aqueous humour (Aq. Humour) samples from patients with PDR compared with non-diabetic patients (controls). b Bar graph quantifying blot (a). A significant decrease was seen in NGF (14 kDa) levels (35% and 65% reduction, respectively) from vitreous and aqueous humour samples of patients with diabetic retinopathy compared with non-diabetic patients; **p < 0.01, n = 6–7. c Representative western blot and statistical analysis (d) of rat retinal samples showing significant accumulation of proNGF levels (twofold) and decreases in NGF levels (50% reduction) from diabetic (D) rat retinas compared with controls. Treatment with atorvastatin (Atorv; 10 mg/kg daily, p.o.) or FeTPPs (Fe; 15 mg/kg daily, i.p.) restored the balance of proNGF and NGF to normal levels. Data are mean ± SEM of six animals in each group; * p < 0.05

Diabetes induces peroxynitrite formation in experimental and human samples

Slot-blot analysis of human aqueous humour samples from PDR patients showed a 1.9-fold increase in 4-HNE adduct formation (a marker of oxidative stress) and a 1.8-fold increase in nitrotyrosine formation (a marker of peroxynitrite) compared with non-diabetic controls (Fig. 2b, d). Similarly, slot-blot analysis of rat retinal homogenate revealed ∼1.4- and 1.6-fold increases in 4-HNE and nitrotyrosine, respectively, compared with controls (Fig. 2a, c). Treatment with atorvastatin exerted similar protective effects to those of FeTPPs in blocking the increases in retinal oxidative stress and peroxynitrite formation.

Diabetes increases oxidative and nitrative stress markers in human and rat retinas. a Slot-blot analysis of retinal homogenate shows ∼1.4-fold increase in 4-HNE adduct formation in experimental diabetes and (b) ∼1.9-fold increase in 4-HNE in aqueous humour samples from PDR patients compared with non-diabetic controls. c Slot-blot analysis of retinal homogenate shows ∼1.6-fold increase in nitrotyrosine (NY) in experimental and ∼1.8-fold increase in NY in (d) aqueous humour samples from PDR patients compared with non-diabetic controls. Treatment (a, c) of diabetic animals (D) with atorvastatin (Atorv; 10 mg/kg daily, p.o.) blocked these effects. Fe, FeTPPs (15 mg/kg daily, i.p.). Data, given as relative optical density (ROD), are means±SEM; n = 6; † p < 0.02

Diabetes stimulates proNGF accumulation in activated retinal Müller cells

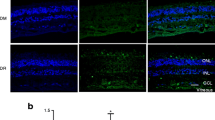

We evaluated the effect of diabetes-induced peroxynitrite on glial activation and found that Müller cells are activated, not astrocytes. This activation was indicated by prominent labelling of GFAP in diabetic retinas, which extended from the nerve fibre layer and inner plexiform layer into the outer nuclear layer of the retina as compared with controls. Treatment of diabetic animals with atorvastatin or FeTPPs blocked this effect (Fig. 3a). In addition, we investigated whether proNGF is secreted by glia in response to diabetes. Compared with controls, diabetic retinas showed prominent immunostaining of proNGF (green), which co-localised with Müller cells (red) labelled with CRALBP (Fig. 3b). Treatment with atorvastatin or FeTPPs markedly reduced the increases in proNGF. The role of diabetes-induced peroxynitrite in activating Müller cells to secrete proNGF was further confirmed using an in vitro approach. rMC-1 were maintained in high glucose (30 mmol/l) for 72 h, after which immunofluorescence of nitrotyrosine showed a 1.8-fold increase in peroxynitrite formation compared with normal glucose control medium (5 mmol/l) (Fig. 3c). Treatment with FeTPPs (2.5 μmol/l) or with atorvastatin (1 μmol/l) blocked the increases in nitrotyrosine formation. We next evaluated the effects of high glucose on proNGF secretion in conditioned medium of Müller cells. Cells maintained in high glucose for 72 h or stimulated with exogenous peroxynitrite (100 μmol/l) for 18 h showed two- and threefold increases of proNGF compared with cells cultured in normal glucose, respectively (Fig. 3d). The action of high glucose was completely blocked by treatment with FeTPPs or atorvastatin (Fig. 3e). Together, these data suggest that diabetes-induced oxidative stress and peroxynitrite activate retinal Müller cells to secrete proNGF.

Diabetes and high glucose activate Müller cells to secrete proNGF. a Representative images showing that while astrocytes were equally labelled with GFAP in diabetic, control or diabetic (D) retinas treated with atorvastatin or FeTPPs, Müller cells were prominently labelled with GFAP in the diabetic group only. Similar observations were detected in other retinas (n = 5 per group). Magnification ×200, scale bar 25 μm. b Representative images showing distribution and colocalisation of proNGF (green) and CRALBP (red) in different retinal layers: the ganglion cell layer (GCL), the inner plexiform layer (IPL), inner nuclear layer (INL) and the outer nuclear layer (ONL). Diabetic retinas showed prominent proNGF accumulation within glia (yellow) compared with controls, which was blocked by treatment of diabetic (D) animals with atorvastatin (10 mg/kg daily, p.o.) or FeTPPs (15 mg/kg daily, i.p.). Similar observations were detected in other retinas (n = 5 per group), magnification, ×200, scale bar 25 μm. c Retinal Müller cells (rMC-1) maintained in high glucose (HG, 30 mmol/l) for 72 h showed significant increases in peroxynitrite (1.8-fold) as indicated by nitrotyrosine formation compared with cells maintained in normal glucose (NG, 5 mmol/l). Co-treatment of high glucose with atorvastatin (Atorv; 1 μmol/l) blocked the increases in peroxynitrite to a similar extent to that achieved by the specific peroxynitrite decomposition catalyst, FeTPPs (Fe; 2.5 μmol/l). d High glucose and peroxynitrite (PN) stimulated proNGF release and accumulation in conditioned medium of rMC-1 cells. Cells were maintained in high glucose (HG; 30 mmol/l) for 72 h or exogenous PN (100 μmol/l) for 18 h. e Blocking of peroxynitrite formation reduced proNGF release in rMC-1 cells. Treatment of cells with atorvastatin (Atorv; 1 μmol/l) or FeTPPs (Fe; 2.5 μmol/l) significantly reduced the release and accumulation of proNGF (32 kDa) in conditioned medium of HG-treated cells. ROD, relative optical density. Data are the mean ± SEM of four cultures in each group; * p < 0.05

Diabetes-induced peroxynitrite impairs MMP-7 activity in clinical and experimental diabetic retinopathy

ProNGF can be proteolytically cleaved to the mature NGF by extracellular MMP-7. Therefore, we determined its abundance and activity in diabetic rat retinas, cultured Müller cells and aqueous humour samples from PDR patients. Western blot analysis showed that diabetic rat retinas had significantly diminished levels (35% less) of MMP-7 compared with controls (Fig. 4a). Treatment of diabetic rats with FeTPPs or atorvastatin restored MMP-7 to normal levels. These results were confirmed by in vitro studies with Müller cell cultures showing that high glucose or peroxynitrite cause significant reduction in MMP-7 levels compared with normal glucose controls (Fig. 4b). However, concurrent treatment of high glucose with atorvastatin (1 μmol/l) blunted the effects of high glucose and restored MMP-7 production. Determination of MMP-7 activity using FRET assay in conditioned medium of peroxynitrite or high glucose-treated Müller cells showed 40 and 60% reduction of MMP-7 activity, respectively (Fig. 4c). Concurrent treatment of high glucose with FeTPPs or atorvastatin restored MMP-7 activity. We further confirmed the clinical significance of our finding by measuring the activity of MMP-7 in aqueous humour samples from PDR patients. In fact, diabetes reduced MMP-7 activity by 50% compared with non-diabetic samples (Fig. 4d).

Diabetes impairs MMP-7 production and activity in clinical and experimental models. a Western blot analysis of retinal lysate showed a significant reduction (35%) of MMP-7 levels in diabetic retinas compared with controls. Treatment of diabetic animals with FeTPPs (Fe; 2.5 μmol/l) and atorvastatin (Atorv; 1 μmol/l) restored MMP-7 to normal levels. b Western blot analysis of rMC-1 lysate showed a significant reduction (35%) of MMP-7 levels in cells maintained in high glucose (HG; 30 mmol/l) for 72 h or peroxynitrite (PN; 100 μmol/l) for 18 h compared with cells maintained in normal glucose (NG; 5 mmol/l). Atorvastatin (1 μmol/l) treatment of cultures maintained in high glucose restored MMP-7 to normal levels. ROD, relative optical density. c FRET assay showed significant reduction of MMP-7 activity in rMC-1 cultures maintained in high glucose (HG) for 72 h or in peroxynitrite (PN) for 18 h compared with cells maintained in normal glucose (NG). Treatment with atorvastatin (Atorv; 1 μmol/l) or FeTPPs (Fe; 2.5 μmol/l) restored MMP-7 to normal levels. a–c Data are the mean ± SEM of four cultures in each group. * p < 0.05. d FRET assay showed significant 50% reduction in MMP-7 activity in human aqueous humour samples from PDR patients compared with non-diabetic controls. n = 4; * p < 0.05

Diabetes stimulates Rho kinase and p38MAPK activation in experimental and human samples

We next evaluated the activation of Rho kinase and p38MAPK as a common signalling pathway implicated in vascular permeability and neuronal death. Activation of Rho kinase by pull-down assay showed significant increases in active RhoA kinase in diabetic retinas from rats (1.8-fold) and humans (1.9-fold) compared with non diabetic controls (Fig. 5a, b). Treatment of diabetic animals with FeTPPs or atorvastatin blocked the increases in active RhoA. Western blot analysis showed significant increases in p38MAPK activation in diabetic retinas from rats (1.54-fold) and humans (1.6-fold) compared with non-diabetic controls (Fig. 5c, d). Treatment of animals with atorvastatin blocked this effect.

Diabetes causes activation of RhoA and p38MAPK in human and rat retinas. a Pull-down assay of active RhoA showing ∼1.8-fold increase in diabetic rat retinas (experimental diabetes) and (b) ∼1.9-fold increase in human retinas of patients with diabetic retinopathy (DR) compared with non-diabetic controls. Treatment (a) with atorvastatin (Atorv; 10 mg/kg daily, p.o.) or FeTPPs (Fe; 15 mg/kg daily, i.p.) significantly reduced active RhoA in diabetic animals but not in controls. c Western blot analysis of the phosphorylation (P) of p38MAPK showing that diabetes significantly increased phosphorylation of p38MAPK (∼1.6 fold) in retinas from rat models of diabetes and (d) in human retinas of patients with diabetic retinopathy (DR) compared with non-diabetic controls. Treatment (c) with atorvastatin or FeTPPs blocked the increase in phosphorylation of p38MAPK in diabetic animals but not in controls. Data, given as relative optical density (ROD), are mean ± SEM of six animals in each group; *p < 0.05

Atorvastatin prevents diabetes-induced retinal neurodegeneration

We have previously shown the neuroprotective effects of FeTPPs in diabetic rat retina [1]. Similarly to our previous findings, quantitative analysis of TUNEL horseradish peroxidase-labelled cells in whole-mounted retinas showed a sevenfold increase in retinal neuronal cell death, which was blocked by treatment with atorvastatin (Fig. 6a). We confirmed neuronal cell death, which was blocked by treatment with atorvastatin, by staining frozen sections with TUNEL-FITC, which showed scattered TUNEL-positive cells in the ganglion cell and inner nuclear layers of diabetic rat retinas (Fig. 6b).

Neuroprotective and BRB-preserving effects of blocking peroxynitrite in experimental diabetes. a Quantitative analysis of total number of TUNEL horseradish peroxidase-positive cells counted in each retina, expressed per 0.5 cm2. The diabetic retinas had significantly more TUNEL horseradish peroxidase-positive cells than the control and atorvastatin-treated groups. Treatment with atorvastatin (10 mg/kg daily, p.o.) blocked cell death in the diabetic (D) retinas, but did not alter number of TUNEL-positive cells in controls. b Representative images of retinal sections with TUNEL labelling from diabetic rats (4 weeks) in different retinal layers. TUNEL-positive cells (arrows) were distributed mainly in the ganglion cell layer (GCL) and inner retinal layers. IPL, inner plexiform layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; ONL, outer nuclear layer. c Representative images of albumin extravasation in different retinal layers. Magnification (b, c) ×200; scale bars 25 μm. d Morphometric analysis of fluorescence intensity in serial sections of rat eyes showed that diabetic rats had a 2.2-fold increase in fluorescence compared with controls. Treatment of diabetic rats (D) with FeTPPs (15 mg/kg daily, i.p.) or atorvastatin (Atorv; 10 mg/kg daily, p.o.) blocked the permeability increase in diabetic animals. Data are the mean ± SEM of six to seven animals in each group. ***p < 0.001

Diabetes-induced peroxynitrite formation causes BRB breakdown

We have previously shown that diabetes causes BRB breakdown in streptozotocin-induced animal models of diabetes [3, 12, 13]. However, the causal role of peroxynitrite has not been investigated. Hence, we performed quantitative analysis using serial image analysis of retinal fluorescence intensity that was normalised to plasma fluorescence intensity for each animal. The results showed ∼2.4-fold increase in fluorescence intensity in diabetic retinas compared with controls. Representative images showed diffuse and prominent fluorescence throughout the diabetic retinal parenchyma (Fig. 6c). Treatment with FeTPPs exerted similar vascular protective effects to those of atorvastatin and prevented diabetes-induced BRB breakdown.

Discussion

The major novel findings of this study are: (1) diabetes-induced peroxynitrite impairs the homeostasis of NGF by inhibiting the proteolytic enzyme, MMP-7, leading to accumulation of proNGF and reduction of mature NGF; (2) increased proNGF is associated with activation of RhoA and p38MAPK in human and rat retinas, leading to accelerated retinal neuronal cell death and BRB breakdown; and (3) co-treatment of diabetic animals with the peroxynitrite decomposition catalyst FeTPPs or atorvastatin normalised the balance of proNGF and NGF, and prevented neuronal death and vascular permeability. A schematic presentation of the proposed mechanism is depicted in Fig. 7.

Schematic figure summarising findings of the current study. It shows that diabetes-induced peroxynitrite causes inhibition of MMP-7, leading to accumulation of proNGF at the expense of mature NGF. Activation of the common RhoA and p38MAPK pathway can lead to neuronal cell death and vascular permeability

A growing body of evidence supports the concept that diabetes disturbs homeostasis in the retina by activating glial cells, reducing neurotrophic and prosurvival inputs, and increasing proinflammatory cytokines, leading to accelerated cell death and vascular permeability, thus impairing vision, notions which have been reviewed previously [18–20]. In agreement, we and others have reported that increases in proinflammatory cytokines, including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), NGF, TNF-α, intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and inducible nitric oxide synthase, in diabetic retinas were correlated with neuronal cell death and vascular permeability [1, 3, 12, 13, 21–23]. However, the role of neurotrophins in the diabetic eye remains unknown. Neurotrophins, including NGF, are secreted by glia as proforms (proNGF) that are proteolytically cleaved to mature ligands (NGF), exerting beneficial effects. Until recently, our knowledge of the release of neurotrophins in diabetic tissue had been limited to techniques such as ELISA assays and quantitative measurement of mRNA expression that could not differentiate proNGF from mature NGF. We and others have reported significant increases of NGF levels in diabetic rat retinal ganglia and serum/tears of patients with diabetic retinopathy [1, 6, 7]. Recently, the development and availability of specific antibodies for proNGF and mature NGF have facilitated a better understanding of neurotrophin release under pathological conditions. Analyses of NGF and proNGF from vitreous and aqueous humour samples from patients with >10 or >25 years of diabetes showed significant (three- or fivefold) accumulation of proNGF and 35% or 65% reduction of mature NGF compared with non-diabetic patients. Interestingly, patients with PDR underwent panretinal photocoagulation, which can induce release of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, but not VEGF and SDF stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1) [24]. However, the possible effects of panretinal photocoagulation on modulation of proNGF remain elusive. The imbalance between proNGF and NGF observed by us in diabetic human samples was also detected in rat retina lysate after 4 weeks of diabetes. In parallel, analysis of oxidative stress and peroxynitrite markers showed significant increases in 4-HNE adducts and nitrotyrosine formation in aqueous humour samples from diabetic patients and diabetic rat retinas compared with non-diabetic controls. These results lend further support to previous studies showing enhanced peroxynitrite formation in clinical and experimental diabetes [1, 3, 12, 22]. Treatment of our diabetic animals with atorvastatin exerted similar protective effects to FeTPPs in reducing peroxynitrite and 4-HNE adducts, as well restoring the balance between NGF and proNGF to normal levels. Accumulation of proNGF after injury has been detected in several diseases of the central nervous system such as Alzheimer’s, where pro-oxidative and pro-inflammatory milieus can reduce protease activity and NGF cleavage [8, 9]. Of note, we believe that this is the first report showing clinical and experimental evidence of significant accumulation of proNGF in the diabetic eye.

Our recent findings demonstrating the critical role of peroxynitrite in the paradox of accelerated neuronal and vascular death despite the significant increases in NGF and VEGF expression [1, 11, 25] prompted us to further characterise the role of peroxynitrite in gliosis and NGF release in the early stages of diabetic retinopathy. Peroxynitrite produced by glia cells is not toxic by itself, but causes activation and expression of proinflammatory cytokines. Supporting this, our previous studies have shown that Müller cells are not among the retinal cell population undergoing apoptosis at 4 weeks of diabetes [1]. Instead, our current study demonstrated that Müller cells are activated, as evidenced by GFAP immunoreactivity and prominent colocalisation of proNGF at the end feet of Müller cells in diabetic rat retinas. The notion that Müller cells are activated, in response to diabetes-induced peroxynitrite, to secrete proNGF was further supported by in vitro results showing significant increases in proNGF levels in rMC-1 conditioned medium in response to high glucose or peroxynitrite, as well as inhibitory effects of FeTPPs or atorvastatin. Our results lend further support to previous studies demonstrating that peroxynitrite activated brain astrocytes to release proNGF [26, 27]. In addition to Müller cells, activated microglial cells can produce proNGF leading to neuronal death [28, 29]. Whether retinal microglial cells play a role in the initial proNGF secretion or sustain a regulatory loop of neurotrophin production during diabetic retinopathy remains to be explored.

While proNGF is cleaved intracellularly by furin, with mature NGF being trafficked to secretory vesicles [9], it is cleaved extracellulary by MMP-7 [8]. Unlike most other family members of MMPs, MMP-7 is constitutively expressed by most adult tissue and its activity is redox-regulated [30]. Hence it is conceivable to expect decreased protease activity under oxidative stress and inflammatory conditions. Our results showed diminished expression and activity of MMP-7 in diabetic retinas or in high glucose-treated Müller cells that were restored by FeTPPs or atorvastatin treatment. Supporting this, previous studies demonstrated diminished expression and activity of MMP-7 in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats [31] and in vitro models in response to hyperglycaemia [32], or oxidative stress via oxidation of active sites of MMP-7 [33]. Moreover, the activity of MMP-7 in aqueous humour samples from PDR patients showed a 50% reduction of MMP-7 activity. Interestingly, two human samples were excluded because of concurrent statin treatment and showed higher MMP-7 than samples from patients not on anti-hyperlipidaemia therapy. The role of peroxynitrite in modulating furin activity and hence intracellular cleavage of proNGF remains elusive and warrants future studies.

While mature NGF mediates neuronal cell survival through binding TrkA and p75NTR receptors, proNGF can promote neuronal apoptosis through binding p75NTR, as reviewed previously [34, 35]. In support of this, our previous work showed significant impairment of TrkA receptor function and upregulation of p75NTR levels in diabetic retinas from humans and rats [1], favouring activation of the latter in response to accumulated proNGF. It has been shown that overabundance of p75NTR constitutively activates RhoA, leading to neuronal death via activation of p38MAPK pathway in response to proNGF [28, 36–39]. In agreement with this, our results showed significant increases in active RhoA as well as p38MAPK in human and experimental diabetic retinas compared with non-diabetic controls (Fig. 5). Treatment of diabetic animals with FeTPPs or atorvastatin blunted these effects. RhoA is a major small GTP-binding protein that acts as a molecular switch to control a large variety of signal transduction pathways. In addition to its role in modulating neuronal survival, RhoA and its downstream target, p38MAPK, are involved in regulation of cell motility via reorganisation of the actin cytoskeleton and, as such, play a critical role in BRB breakdown [40–42]. Under diabetic conditions, BRB breakdown is thought to occur because of diabetes-induced oxidative and nitrative stress, resulting in increased activity of proinflammatory cytokines including VEGF and TNF-α, thus activating p38MAPK [1, 3, 12, 38, 43, 44]. Here, we show a potential role for proNGF as a new player that possibly causes BRB breakdown by directly activating the RhoA and p38MAPK pathway in vasculature or indirectly by causing neuronal death in the diabetic retina. Further studies involving the role of proNGF in BRB breakdown and elucidating the downstream signalling events are currently in progress by our group.

The current study investigated the neurological and vascular effects of two different drugs in diabetic animals: (1) the peroxynitrite decomposition catalyst FeTPPs, and (2) the lipid-lowering drug, atorvastatin. Although the results of the two drugs were in parallel, the neuro and vascular protective effects of atorvastatin were usually superior to those of FeTPPs, but did not reach significance, a fact possibly attributable to the pleiotropic effects of statins, including antioxidant effects and inhibition of GTP-binding proteins, in addition to their known cholesterol-lowering ability [13, 17, 45–48]. While previous studies examined the protective effects of statins in retinas from ischaemia/reperfusion models or in other tissue from diabetic animals, our study is the first to demonstrate the neuroprotective effects of atorvastatin in the diabetic retina. Although, the neuro and vascular protective effects of FeTPPs are significant, its therapeutic use is limited due to chronic administration of iron. On the other hand, the results of oral atorvastatin treatment were generated using a dose that produces peak plasma concentrations similar to those reported after 60–80 mg/day of atorvastatin in humans, and hence could be readily translated to patients with diabetic retinopathy [45].

Abbreviations

- BRB:

-

Blood–retinal barrier

- FeTPPs:

-

5,10,15,20-Tetrakis (4-sulfonatophenyl)porphyrinato iron (III) chloride

- GFAP:

-

Glial fibrillary acidic protein

- 4-HNE:

-

4-Hydroxy-2-nonenal

- MMP-7:

-

Matrix metalloproteinase-7

- NGF:

-

Nerve growth factor

- p38MAPK:

-

p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase

- PDR:

-

Proliferative diabetic retinopathy

- p.o.:

-

Per os (by oral gavage)

- proNGF:

-

Proform of NGF

- rMC-1:

-

Retinal Müller glial cell line culture cells

- TrkA:

-

Tyrosine receptor kinase A

- VEGF:

-

Vascular endothelial growth factor

References

Ali TK, Matragoon S, Pillai BA, Liou GI, El-Remessy AB (2008) Peroxynitrite mediates retinal neurodegeneration by inhibiting NGF survival signal in experimental and human diabetes. J Diabetes 57:889–898

Barber AJ, Lieth E, Khin SA, Antonetti DA, Buchanan AG, Gardner TW (1998) Neural apoptosis in the retina during experimental and human diabetes. Early onset and effect of insulin. J Clin Invest 102:783–791

El-Remessy AB, Al-Shabrawey M, Khalifa Y, N-t T, Caldwell RB, Liou GI (2006) Neuroprotective and blood-retinal barrier-preserving effects of cannabidiol in experimental diabetes. Am J Pathol 168:235–244

Adamis AP, Miller JW, Bernal MT et al (1994) Increased vascular endothelial growth factor levels in the vitreous of eyes with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol 118:445–450

Ali TK, El-Remessy AB (2009) Diabetic retinopathy: current management and experimental therapeutic targets. Pharmacotherapy 29:182–192

Azar ST, Major SC, Safieh-Garabedian B (1999) Altered plasma levels of nerve growth factor and transforming growth factor-beta2 in type-1 diabetes mellitus. Brain Behav Immun 13:361–366

Park KS, Kim SS, Kim JC et al (2008) Serum and tear levels of nerve growth factor in diabetic retinopathy patients. Am J Ophthalmol 145:432–437

Lee R, Kermani P, Teng KK, Hempstead BL (2001) Regulation of cell survival by secreted proneurotrophins. Science (New York, NY) 294:1945–1948

Hempstead BL (2009) Commentary: regulating proNGF action: multiple targets for therapeutic intervention. Neurotox Res 16:255–260

Yoshida Y, Yamagishi SI, Matsui T et al (2009) Protective role of pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) in early phase of experimental diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes/Metab Res Rev 25:678–686

Abdelsaid MA, Pillai BA, Matragoon S, Prakash R, Al-Shabrawey M, El-Remessy AB (2010) Early intervention of tyrosine nitration prevents vaso-obliteration and neovascularization in ischemic retinopathy. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 332:125–134

El-Remessy AB, Behzadian MA, Abou-Mohamed G, Franklin T, Caldwell RW, Caldwell RB (2003) Experimental diabetes causes breakdown of the blood-retina barrier by a mechanism involving tyrosine nitration and increases in expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and urokinase plasminogen activator receptor. Am J Pathol 162:1995–2004

Al-Shabrawey M, El-Remessy AB, Ma G et al (2008) Mechanisms of statin’s protective actions in diabetic retinopathy: role of NAD(P)H oxidase and STAT3. IOVS 49:3231–3238

Linseman DA, Loucks FA (2008) Diverse roles of Rho family GTPases in neuronal development, survival, and death. Front Biosci 13:657–676

Sarthy VP, Brodjian SJ, Dutt K, Kennedy BN, French RP, Crabb JW (1998) Establishment and characterization of a retinal Muller cell line. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci 39:212–216

El-Remessy AB, Abou-Mohamed G, Caldwell RW, Caldwell RB (2003) High glucose-induced tyrosine nitration in endothelial cells: role of eNOS uncoupling and aldose reductase activation. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci 44:3135–3143

Romero MJ, Platt DH, Tawfik HE et al (2008) Diabetes-induced coronary vascular dysfunction involves increased arginase activity. Circ Res 102:95–102

Antonetti DA, Barber AJ, Bronson SK et al (2006) Diabetic retinopathy: seeing beyond glucose-induced microvascular disease. Diabetes 55:2401–2411

Fletcher EL, Phipps JA, Wilkinson-Berka JL (2005) Dysfunction of retinal neurons and glia during diabetes. Clin Exp Optom 88:132–145

Gardner TW, Antonetti DA, Barber AJ, LaNoue KF, Levison SW (2002) Diabetic retinopathy: more than meets the eye. Surv Ophthalmol 47(Suppl 2):S253–S262

Drel VR, Pacher P, Ali TK et al (2008) Aldose reductase inhibitor fidarestat counteracts diabetes-associated cataract formation, retinal oxidative-nitrosative stress, glial activation, and apoptosis. Int J Mol Med 21:667–676

Du Y, Smith MA, Miller CM, Kern TS (2002) Diabetes-induced nitrative stress in the retina, and correction by aminoguanidine. J Neurochem 80:771–779

Joussen AM, Poulaki V, Le ML et al (2004) A central role for inflammation in the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy. FASEB J 18:1450–1452

Shimura M, Yasuda K, Nakazawa T et al (2009) Panretinal photocoagulation induces pro-inflammatory cytokines and macular thickening in high-risk proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 247:1617–1624

El-Remessy AB, Bartoli M, Platt DH, Fulton D, Caldwell RB (2005) Oxidative stress inactivates VEGF survival signaling in retinal endothelial cells via PI 3-kinase tyrosine nitration. J Cell Sci 118:243–252

Vargas MR, Pehar M, Cassina P, Estevez AG, Beckman JS, Barbeito L (2004) Stimulation of nerve growth factor expression in astrocytes by peroxynitrite. In Vivo 18:269–274

Domeniconi M, Hempstead BL, Chao MV (2007) Pro-NGF secreted by astrocytes promotes motor neuron cell death. Mol Cell Neurosci 34:271–279

Yune TY, Lee JY, Jung GY et al (2007) Minocycline alleviates death of oligodendrocytes by inhibiting pro-nerve growth factor production in microglia after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci 27:7751–7761

Srinivasan B, Roque CH, Hempstead BL, Al-Ubaidi MR, Roque RS (2004) Microglia-derived pronerve growth factor promotes photoreceptor cell death via p75 neurotrophin receptor. J Biol Chem 279:41839–41845

Wielockx B, Libert C, Wilson C (2004) Matrilysin (matrix metalloproteinase-7): a new promising drug target in cancer and inflammation? Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 15:111–115

McLennan SV, Kelly DJ, Schache M et al (2007) Advanced glycation end products decrease mesangial cell MMP-7: a role in matrix accumulation in diabetic nephropathy? Kidney Int 72:481–488

Abdel Wahab N, Mason RM (1996) Modulation of neutral protease expression in human mesangial cells by hyperglycaemic culture. Biochem J 320:777–783

Fu X, Kassim SY, Parks WC, Heinecke JW (2003) Hypochlorous acid generated by myeloperoxidase modifies adjacent tryptophan and glycine residues in the catalytic domain of matrix metalloproteinase-7 (matrilysin): an oxidative mechanism for restraining proteolytic activity during inflammation. J Biol Chem 278:28403–28409

Casaccia-Bonnefil P, Carter BD, Dobrowsky RT, Chao MV (1996) Death of oligodendrocytes mediated by the interaction of nerve growth factor with its receptor p75. Nature 383:716–719

von Bartheld CS (1998) Neurotrophins in the developing and regenerating visual system. Histol Histopathol 13:437–459

Semenova MM, Maki-Hokkonen AM, Cao J et al (2007) Rho mediates calcium-dependent activation of p38alpha and subsequent excitotoxic cell death. Nat Neurosci 10:436–443

Dubreuil CI, Winton MJ, McKerracher L (2003) Rho activation patterns after spinal cord injury and the role of activated Rho in apoptosis in the central nervous system. J Cell Biol 162:233–243

Nwariaku FE, Chang J, Zhu X et al (2002) The role of p38 map kinase in tumor necrosis factor-induced redistribution of vascular endothelial cadherin and increased endothelial permeability. Shock 18:82–85

Nwariaku FE, Rothenbach P, Liu Z, Zhu X, Turnage RH, Terada LS (2003) Rho inhibition decreases TNF-induced endothelial MAPK activation and monolayer permeability. J Appl Physiol 95:1889–1895

Bogatcheva NV, Adyshev D, Mambetsariev B, Moldobaeva N, Verin AD (2007) Involvement of microtubules, p38, and Rho kinases pathway in 2-methoxyestradiol-induced lung vascular barrier dysfunction. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 292:L487–L499

Kahles T, Luedike P, Endres M et al (2007) NADPH oxidase plays a central role in blood-brain barrier damage in experimental stroke. Stroke 38:3000–3006

Guo X, Wang L, Chen B et al (2009) ERM protein moesin is phosphorylated by advanced glycation end products and modulates endothelial permeability. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 297:H238–H246

Poulaki V, Qin W, Joussen AM et al (2002) Acute intensive insulin therapy exacerbates diabetic blood-retinal barrier breakdown via hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha and VEGF. J Clin Investig 109:805–815

Issbrucker K, Marti HH, Hippenstiel S et al (2003) p38 MAP kinase—a molecular switch between VEGF-induced angiogenesis and vascular hyperpermeability. FASEB J 17:262–264

Elewa HF, Kozak A, El-Remessy AB et al (2009) Early atorvastatin reduces hemorrhage after acute cerebral ischemia in diabetic rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 330:532–540

Tawfik HE, El-Remessy AB, Matragoon S, Ma G, Caldwell RB, Caldwell RW (2006) Simvastatin improves diabetes-induced coronary endothelial dysfunction. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 319:386–395

Miyahara S, Kiryu J, Yamashiro K et al (2004) Simvastatin inhibits leukocyte accumulation and vascular permeability in the retinas of rats with streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Am J Pathol 164:1697–1706

Tsubouchi H, Inoguchi T, Sonta T et al (2005) Statin attenuates high glucose-induced and diabetes-induced oxidative stress in vitro and in vivo evaluated by electron spin resonance measurement. Free Radic Biol Med 39:444–452

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to C. Von Bartheld (Department of Physiology and Cell Biology, University of Nevada School of Medicine) for his careful review of the manuscript and helpful insights. This work was supported by the American Heart Association Scientist Development Grant (0530170N to A. B. El-Remessy), a research grant from Pfizer Pharmaceutical, a Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation grant (2-2008-149 to A. B. El-Remessy) and the University of Georgia Research Foundation (to A. B. El-Remessy).

Duality of interest

The authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ali, T.K., Al-Gayyar, M.M.H., Matragoon, S. et al. Diabetes-induced peroxynitrite impairs the balance of pro-nerve growth factor and nerve growth factor, and causes neurovascular injury. Diabetologia 54, 657–668 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-010-1935-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-010-1935-1