Abstract

The seronegative spondyloarthopathies (SpA) share certain common articular and peri-articular features that differ from rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and other forms of inflammatory arthritis. These include the tendency of the SpAs to involve the axial skeleton in addition to the diarthrodial joints, and the prominent involvement of the extra-articular entheses (sites of ligamentous and tendon insertion), which are not common sites of primary pathology in RA and other inflammatory arthropathies. The differential anatomic sites of bone pathology in the SpAs in comparison to the other forms of arthritis suggest that the underlying pathogenic processes and cellular and molecular mechanisms that account for the peri-articular bone pathology involve different underlying disease mechanisms. This review will highlight the molecular and cellular processes that are involved in the pathogenesis of the skeletal pathology in the SpAs, and provide evidence that many of the factors involved in regulation of bone cell function exhibit potent immune-regulatory activity, providing support for the general concept of osteoimmunology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The seronegative spondyloarthopathies (SpA) that include ankylosing spondylitis (AS), reactive arthritis, and arthritis associated with psoriasis or inflammatory bowel disease, and juvenile onset spondyloarthropathy, share certain common articular and peri-articular features that differ from rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and other forms of inflammatory arthritis. These differences include the tendency of the SpAs to involve the axial skeleton in addition to the diarthrodial joints [1, 2], and the prominent involvement of the extra-articular entheses (sites of ligamentous and tendon insertion), which are not common sites of primary pathology in RA and other inflammatory arthropathies. The differential anatomic sites of the articular and peri-articular bone pathology in the SpAs in comparison to the other forms of arthritis suggests that the underlying pathogenic processes that account for the peri-articular inflammation involve different underlying disease mechanisms. Analysis of the inflamed tissues at sites of skeletal pathology support this hypothesis, in that the cell types and profiles of inflammatory mediators differ in the SpAs in comparison to RA and other forms of inflammatory arthritis. Many of the mediators involved in the de-regulation of bone cell activity in the SpAs and RA also function as potent regulators of the immune system. This observation has led to the development of a specialized field of investigation that is generally identified as “osteoimmunology”. This review will highlight the molecular and cellular processes that are involved in the pathogenesis of the skeletal pathology in the SpAs, and provide evidence that many of the factors involved in regulation of bone cell function exhibit potent immune-regulatory activity, providing support for the general concept of osteoimmunology.

Mechanisms of Physiological Bone Adaptation and Remodeling

Peri-articular bone is organized into distinct structural entities that include the subchondral bone plate, which is comprised of compact cortical bone, and a deeper zone of contiguous trabecular bone that is encased within the bone marrow. The bone that forms the joint margins and extends distally from the joint surface is also comprised of compact bone that is lined by the periosteum. The peri-articular bone at all of these sites undergoes marked changes in response to biological and biomechanical signals produced by the local inflammatory processes associated with the SpAs. These bone changes are mediated by bone cells that modify the architecture and properties of the bone through active cellular processes of modeling and remodeling [3]. Modeling is a process that involves direct osteoblast-mediated apposition of bone to existing bone surfaces without a resorptive phase. Remodeling involves the recruitment of monocytic osteoclast precursors to the bone surface followed by differentiation of these cells into osteoclasts that are uniquely adapted to removal of the mineralized bone matrix. Multiple lines of evidence have established that the osteoclast is required for resorption of bone under physiologic conditions of bone remodeling [4, 5]. The role of the osteoclast in pathologic states associated with SpA and other forms of inflammatory arthritis will be discussed in a subsequent section.

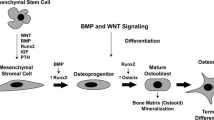

In the remodeling cycle, the phase of osteoclast-mediated bone resorption is followed by a so-called reversal phase after which the resorbed bone surface is populated by precursors of the osteoblast, which are of mesenchymal origin. The osteoblast lineage cells then undergo differentiation into mature bone-forming osteoblasts that replace the resorbed bone. Remodeling occurs during embryonic development and throughout post-natal life, and provides a cellular system for adapting bone to biomechanical influences, repairing damage to the bone matrix and, under certain conditions, releasing calcium for maintenance of mineral ion homeostasis. Importantly, under physiological conditions, the amount of bone that is removed during the phase of bone resorption is exactly matched by the amount of bone that is added during the phase of bone formation, such that bone mass is preserved during the remodeling cycle. The mechanisms that are involved in the “coupling” of the bone resorption and formation are not fully understood. Both transforming factor-β (TGF-β) and bone morphogenic proteins (BMP) are growth factors that are sequestered within the bone matrix during osteoblast-mediated bone formation, and their release during the phase of osteoclast-mediated bone resorption represents a potential mechanism for linking the resorptive process to bone formation [6, 7]. There is also evidence that osteoclasts may themselves be the source of factors that can function either as inhibitors or activators of osteoblast differentiation and activity [8•, 9]. In the SpAs, the so-called “coupling” of bone formation and resorption is de-regulated such that there is localized loss of bone in the entheseal insertion sites and excessive bone formation in periosteal sites adjacent to the sites of bone erosion.

Etheseal inflammation is a unique feature of the SpAs that results in characteristic skeletal pathological changes. At these sites, the new bone is added by a process of endochondral ossification that recapitulates the cellular mechanisms of bone growth that occur during skeletal growth and development in which new bone is formed by replacement of a cartilaginous matrix. Syndesmophytes, which are one of the radiographic hallmarks of the SpAs, represent examples of ossification at the margins of vertebral bodies that are formed via the process of endochondral ossification [10]. Local production of bone growth factors, including TGF-β and BMPs, which play a role in endochonral bone formation during development and post-natally in fracture repair, have been implicated in this process [10–14].

Recent studies have identified the role of the osteocyte in contributing to the regulation of bone remodeling [15•, 16•]. These cells are the most abundant bone cell type. They are embedded within the bone matrix where they form an interconnected network with each other and with the cells on the bone surface. In response to mechanical signals, local soluble mediators and systemic hormones release products that control the activities of the osteoclasts and osteoblasts involved in the remodeling process. Two of these osteocyte-derived products, receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL) and sclerostin, play essential roles in regulating bone remodeling. RANKL was originally identified as TNF-related activation-induced cytokine (TRANCE) that regulated dendritic cell activity and played a role in development of the immune system [17, 18]. Subsequently, RANKL was shown to be a master regulator of osteoclast differentiation that was required for formation of osteoclasts and bone resorption [19, 20]. Production of RANKL by osteocytes enhances osteoclast-mediated bone resorption in response to mechanical stimuli and hormones such as parathyroid hormone [15•, 16•].

Sclerostin is a product of the sost gene, which is a potent inhibitor of the Wnt/βcatenin signaling pathway that contributes to the regulation of bone formation [21]. The expression of this gene is regulated in part by mechanical factors and soluble mediators such as prostaglandins [22•, 23, 24]. The Dickkopf (DKK) family of proteins, which are produced by a variety of cell types, also inhibit bone formation by interfering with signaling by the Wnt/βcatenin pathway [21, 25•]. Both DKK-1 and sclerostin, as well as soluble frizzled related protein (sFRP), which binds Wnt ligands involved in activation of the Wnt/βcatenin pathway, are implicated in the suppression of bone repair in RA. As will be discussed in the following section, the reduced production of these inhibitors of bone formation likely contributes to the excessive bone formation that characterizes the skeletal pathology in the SpAs.

Mechanisms of Pathological Bone Remodeling in the SpAs

Investigators have utilized MRI and anatomic and histopathological analysis to examine the pathological changes at the entheses, which are primary sites of inflammation in the SpAs [12, 26, 27, 28•]. The inflammatory tissue often extends to the synovial lining, which exhibits synovial hyperplasia, lymphocytic infiltration, and pannus formation. The development of synovial pannus and entheseal inflammation is also accompanied by inflammatory cell infiltration in the subchondral bone marrow [29]. Cells with morphological features of osteoclasts can be identified at the interface between the bone surface and the inflammatory tissue associated with bone erosions, providing evidence that, similar to RA, osteoclasts are the cell type responsible for the pathological bone resorption. Studies employing animal models of inflammatory arthritis in which osteoclast formation is defective have helped to provide strong evidence that osteoclasts are the principal cell type responsible for the pathological bone resorption in inflammatory arthropathies. Pettit et al. generated inflammatory arthritis in mice lacking the gene for RANKL [30]. They showed that the RANKL knock-out mice, which lacked the capacity to form osteoclasts, were protected from the development of bone erosions despite a level of synovial inflammation comparable to the wild-type mice. Subsequently, other investigators [31, 32] provided further evidence demonstrating the requirement for osteoclasts in the pathogenesis of bone erosions utilizing additional murine models of inflammatory arthritis.

As described in the preceding discussion, a striking feature of the skeletal pathology in the SpAs is the presence of enhanced bone formation associated with the entheseal and synovial pathology. Braun [12] analyzed tissues from inflamed sacroiliac joints obtained from patients with AS, and noted the presence of dense infiltrates of CD14 positive macrophages and CD4+ and CD8T+ lymphocytes. They also observed localized nodules of endochondral ossification within the inflamed tissues. Analysis, using in situ hybridization, revealed that many of the inflammatory cells expressed abundant messenger RNA for tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), but not interleukin IL-1β (IL-1β). Of interest, TGF-β2 message was noted in close proximity to the regions of new bone formation. More recently, Lories et al. [13] examined synovial biopsies from patients with AS and RA and detected high levels of BMP-2 and -6 expression in synovial fibroblasts and macrophages. They also showed that treatment of synovial fibroblasts with TNF-α or IL-1 increased BMP-2 and BMP-6 expression, providing a potential mechanism for the enhanced production of these bone growth factors in the inflamed synovial tissues. The detection of the bone growth factors in the RA synovium was surprising in light of the absence of new bone formation at sites of synovial pathology in RA, and they speculated that the suppression of bone repair could be related to the production in the RA synovium of potent factors that inhibit osteoblast-mediated bone formation.

Diarra and co-workers [33] have provided insights into the mechanism responsible for the suppressed bone formation and repair associated with the synovial lesion in RA using animal models of RA. Analysis of inflamed synovial tissues in animals with arthritis revealed high levels of expression of DKK-1, the potent inhibitor of the Wnt/βcatenin pathway. They also analyzed synovial tissue from RA patients and found that DKK-1 was expressed in synovial fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and in chondrocytes located in cartilage immediately adjacent to sites of pannus invasion. Using in vitro cell cultures they showed that TNF-α markedly increased the production of DKK-1 in cultured synovial fibroblasts. Analysis of the serum levels of DKK-1 in RA patients revealed that DKK-1 levels were elevated in RA patients compared to healthy controls, and that DKK-1 levels correlated with measures of clinical disease activity. In contrast, in patients with AS, the serum DKK-1 levels were below the levels in the healthy control population. In studies by Diarra et al. [33], treatment of animals with arthritis with an antibody to DKK-1 resulted in increased bone repair, but in addition they unexpectedly observed a marked inhibition in focal articular bone resorption. The effect on bone resorption was attributed to an increase in the production of osteoprotegerin (OPG), the potent inhibitor of RANKL. They speculated that the increase in OPG was related to inhibition of DKK-1 and resultant up-regulation of the Wnt pathway that led to activation of βcatenin, which transcriptionally enhances OPG gene expression [33, 34].

Walsh et al. extended the observations of Diarra using the serum transfer model of arthritis [35]. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction was used to evaluate the expression levels of a spectrum of Wnt pathway inhibitors in retrieved synovial specimens from arthritic and wild type animals. They showed that the levels of several members of the DKK-1 family, as well as the soluble frizzled related protein (sFRP), were elevated in the synovial tissues from animals with arthritis compared to the controls, and employing immunostaining confirmed the local expression of DKK-1 and sFRP1 in synovial tissue at sites of erosions.

Similar to the observations of Diarra et al. [33], Appel and co-workers [11] found that serum levels of DKK-1 were reduced in patients with AS compared to healthy controls. In addition, using serial samples, they showed serum sclerostin levels correlated with the propensity to form syndesmophytes and noted that low serum sclerostin levels were associated with the formation of new syndesmophytes. They also analyzed bone tissue from joints from patients with AS and noted the virtual absence of sclerostin expression in osteocytes at sites of new bone formation, providing further evidence that the lack of suppression of the Wnt/βcatenin signaling contributed to the enhanced bone formation.

A recent publication by Sherlock et al. [28•] provides further evidence of the unique interplay between the bone and immune systems. Employing a murine model of AS, the authors identified the presence of T cells that were responsive to IL-23 in the entheses. IL-23 is a cytokine that previously had been linked to the pathogenesis of both articular and extra-articular inflammation in the SpAs [36, 37]. Importantly, they showed that overexpression of IL-23 was sufficient to induce a destructive enthesitis with histopathologic and bone remodeling features that pheno-copied the features of AS. They found that both IL-17 and IL-22 contributed to the pathology, and that IL-22 was the predominant effector molecule. They further showed that IL-22 could induce osteoblast differentiation via effects on the Wnt and BMP pathways, providing a link between the proinflammatory and immunomodulatory activities of this cytokine and its capacity to modulate bone remodeling and enhance bone formation at sites of inflammation. The bone anabolic effects of IL-22 are not unique to this cytokine, and other proinflammatory cytokines also have been shown to have pro-osteogenic effects. These include, IL-1, IL-17, IL-18, IL-33 and oncostatin M, which under certain conditions can enhance osteoblast differentiation [38–41]. Although the specific mediators have not been rigorously defined, T cells and monocyte–macrophage lineage cells have also been shown to exert pro-osteogenic effects on osteoblast precursors, providing additional evidence that under certain conditions immune cells and their products may contribute not only to catabolic processes but also participate in anabolic tissue responses, at least with respect to bone [42–45].

MRI imaging has been extensively utilized to study the inflammatory bone pathology associated with the SpAs. In these studies, so-called osteitis is manifest by the presence of an increased signal on STIR sequences. The altered signals have been identified in multiple skeletal sites, including the sacroiliac and zygapophyseal joints and the vertebral bodies, where they are most often localized to the endplates or corners of the vertebral bodies [46]. Histopathological examination of tissues from these sites has confirmed the presence of inflammatory cell infiltration with monocyte macrophages and T and B cells accompanied by variable degrees of edema [47–49].

Multiple previously published studies in patients with AS have observed that, although anti-TNF-α therapy effectively suppresses entheseal and synovial inflammation, the treatment does not prevent progression of syndesmophyte formation [50–53]. Some authors have interpreted these findings to suggest that the formation of syndesmophytes following resolution of inflammation after anti-TNF therapy supports the theory that TNF-α acts as a brake on bone formation, and that blockade of its activity releases this constraint and allows new bone formation [54–56]. An alternate explanation is that inflammation and new bone formation may be independent of each other, and that the pathogenic processes responsible for the enhanced bone formation may escape control by the therapies such as anti-TNF-α that suppresses the inflammatory process.

A recent publication by Baraliakos et al. [57•] has provided data on the long-term follow-up of patients with AS treated successfully with anti-TNF therapy. They compared the radiographic progression of syndesmophytes in AS patients treated with infliximab versus historical controls who had not received TNF-blockers over 8 years. Although there were limitations in the study design, their data indicated that there was less new bone formation in patients treated with anti-TNF therapy, and they suggested that the processes of inflammation and new bone formation were in fact linked. They speculated that this argued against the hypothesis of a mechanism for the development of excessive new bone formation that was independent of inflammation.

Paradoxically, although individuals with SpA exhibit localized regions of enhanced bone formation at sites of spinal inflammation, many patients have evidence of marked osteopenia of the spinal column. Studies indicate that disease burden correlates with the osteoporosis and osteopenia and importantly the presence of decreased bone mass is associated with an increased risk of fracture [58, 59]. The bone loss has been ascribed to spinal immobility [60]. However, other studies [61, 62] have demonstrated that osteopenia may occur, even in the absence of bony ankylosis, and the authors speculated that the osteopenia was attributable to local effects of inflammatory mediators released from the sites of joint pathology, rather than immobilization. Of interest, Marzo-Ortega et al. [63] demonstrated that BMD improves in patients with SpA who show clinical responses to the TNF-α blocker, etanercept.

Conclusions

In summary, under physiological conditions, bone remodeling is initiated by activation of osteoclast-mediated bone resorption followed by a phase of osteoblast-mediated bone formation. These cellular processes are tightly “coupled” such that bone structure and mass are preserved during the remodeling cycle. In the SpAs, the cellular machinery of the remodeling unit is co-opted by inflammatory cells and their products, resulting in de-regulation of the remodeling process and uncoupling of bone resorption and formation. A unique feature of the SpAs in comparison to RA is the presence of enhanced bone formation at sites of inflammation. In part, this may be related to the localization of the inflammatory process to the entheses, but, in addition, there is evidence that the cytokine profiles and regulation of the Wnt/βcatenin pathways in the SpAs may differ from the regulatory pathways in RA and other forms of inflammatory arthritis. Many studies have observed that, although inhibition of inflammation with anti-TNF therapy reduces progression of bone erosions at sites of inflammation, enhanced bone formation may persist. The mechanisms involved in this apparent dissociation of inflammation and bone formation have not been fully elucidated. Further studies are needed to confirm these observations and to integrate the findings into improving the treatment protocols for management of the SpAs.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance

Goldring SR, Schett G. The role of the immune system in the bone loss of inflammatory arthritis. In: Lorenzo J, Choi Y, Horowitz M, Takayanagi H, editors. Osteoimmunology. London: Academic Press; 2011. p. 301–24.

Schett G. Effects of inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines on the bone. Eur J Clin Invest. 2011;10:1–6.

Eriksen EF. Cellular mechanisms of bone remodeling. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2010;11(4):219–27.

Teitelbaum S. Bone resorption by osteoclasts. Science. 2000;289:1504–8.

Teitelbaum SL. Osteoclasts: what do they do and how do they do it? Am J Pathol. 2007;170(2):427–35.

Nistala H, Lee-Arteaga S, Siciliano G, et al. Extracellular regulation of transforming growth factor beta and bone morphogenetic protein signaling in bone. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1192:253–6.

Wu X, Shi W, Cao X. Multiplicity of BMP signaling in skeletal development. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1116:29–49.

• Negishi-Koga T, Shinohara M, Komatsu N, et al. Suppression of bone formation by osteoclastic expression of semaphorin 4D. Nat Med. 2011;17(11):1473–80. Role of osteclasts in inhibiting bone formation.

Pederson L, Ruan M, Westendorf JJ, et al. Regulation of bone formation by osteoclasts involves Wnt/BMP signaling and the chemokine sphingosine-1-phosphate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(52):20764–9.

Lories RJ, Luyten FP, de Vlam K. Progress in spondylarthritis. Mechanisms of new bone formation in spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11(2):221.

Appel H, Ruiz-Heiland G, Listing J, et al. Altered skeletal expression of sclerostin and its link to radiographic progression in ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(11):3257–62.

Braun J, Bollow M, Neure L, et al. Use of immunohistologic and in situ hybridization techniques in the examination of sacroiliac joint biopsy specimens from patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;4:499–505.

Lories RJ, Derese I, Ceuppens JL, et al. Bone morphogenetic proteins 2 and 6, expressed in arthritic synovium, are regulated by proinflammatory cytokines and differentially modulate fibroblast-like synoviocyte apoptosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(10):2807–18.

Lories RJ, Derese I, Luyten FP. Modulation of bone morphogenetic protein signaling inhibits the onset and progression of ankylosing enthesitis. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(6):1571–9.

• Nakashima T, Hayashi M, Fukunaga T, et al. Evidence for osteocyte regulation of bone homeostasis through RANKL expression. Nat Med. 2011;17(10):1231–4. Role of osteocytes in regulating bone osteoclast-mediated bone resorption via RANKL production.

• Xiong J, Onal M, Jilka RL, et al. Matrix-embedded cells control osteoclast formation. Nat Med. 2011;17(10):1235–41. Role of osteocytes in regulating bone remodeling.

Anderson DM, Maraskovsky E, Billingsley WL, et al. A homologue of the TNF receptor and its ligand enhance T-cell growth and dendritic-cell function. Nature. 1997;390(6656):175–9.

Wong BR, Josien R, Lee SY, et al. TRANCE (tumor necrosis factor [TNF]-related activation-induced cytokine), a new TNF family member predominantly expressed in T cells, is a dendritic cell-specific survival factor. J Exp Med. 1997;186(12):2075–80.

Lacey DL, Timms E, Tan HL, et al. Osteoprotegerin ligand is a cytokine that regulates osteoclast differentiation and activation. Cell. 1998;93(2):165–76.

Yasuda H, Shima N, Nakagawa N, et al. Identity of osteoclastogenesis inhibitory factor (OCIF) and osteoprotegerin (OPG): a mechanism by which OPG/OCIF inhibits osteoclastogenesis in vitro. Endocrinology. 1998;139(3):1329–37.

Baron R, Rawadi G. Wnt signaling and the regulation of bone mass. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2007;5(2):73–80.

• Galea GL, Sunters A, Meakin LB, et al. Sost down-regulation by mechanical strain in human osteoblastic cells involves PGE2 signaling via EP4. FEBS Lett. 2011;585(15):2450–4. Role of prostaglandins in regulating load-induced bone formation.

Price JS, Sugiyama T, Galea GL, et al. Role of endocrine and paracrine factors in the adaptation of bone to mechanical loading. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2011;9(2):76–82.

Robling AG, Niziolek PJ, Baldridge LA, et al. Mechanical stimulation of bone in vivo reduces osteocyte expression of Sost/sclerostin. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(9):5866–75.

• Baron R, Kneissel M. WNT signaling in bone homeostasis and disease: from human mutations to treatments. Nat Med. 2013;19(2):179–92. Comprehesive review of Wnt pathway and its role in regulating bone remodeling.

Benjamin M, McGonagle D. The enthesis organ concept and its relevance to the spondyloarthropathies. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2009;649:57–70.

McGonagle D. Imaging the joint and enthesis: insights into pathogenesis of psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64 Suppl 2:ii58–60.

• Sherlock JP, Joyce-Shaikh B, Turner SP, et al. IL-23 induces spondyloarthropathy by acting on ROR-gammat+ CD3+CD4-CD8- entheseal resident T cells. Nat Med. 2012;18(7):1069–76. Role of entheseal T cells and IL-22, IL-23 and IL-17 axis in inflammation and de-regulated bone remodeling in SpAs.

Appel H, Kuhne M, Spiekermann S, et al. Immunohistochemical analysis of hip arthritis in ankylosing spondylitis: evaluation of the bone-cartilage interface and subchondral bone marrow. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(6):1805–13.

Pettit AR, Ji H, von Stechow D, et al. TRANCE/RANKL knockout mice are protected from bone erosion in a serum transfer model of arthritis. Am J Pathol. 2001;159(5):1689–99.

Li P, Schwarz EM, O'Keefe RJ, et al. RANK signaling is not required for TNFalpha-mediated increase in CD11(hi) osteoclast precursors but is essential for mature osteoclast formation in TNFalpha-mediated inflammatory arthritis. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19(2):207–13.

Redlich K, Hayer S, Ricci R, et al. Osteoclasts are essential for TNF-alpha-mediated joint destruction. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1419–27.

Diarra D, Stolina M, Polzer K, et al. Dickkopf-1 is a master regulator of joint remodeling. Nat Med. 2007;13(2):156–63.

Goldring SR, Goldring MB. Eating bone or adding it: the Wnt pathway decides. Nat Med. 2007;13(2):133–4.

Walsh NC, Reinwald S, Manning CA, et al. Osteoblast function is compromised at sites of focal bone erosion in inflammatory arthritis. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24(9):1572–85.

Lories RJ, McInnes IB. Primed for inflammation: enthesis-resident T cells. Nat Med. 2012;18(7):1018–9.

Lories RJ, Schett G. Pathophysiology of new bone formation and ankylosis in spondyloarthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2012;38(3):555–67.

Kato-Kogoe N, Nishioka T, Kawabe M, et al. The promotional effect of IL-22 on mineralization activity of periodontal ligament cells. Cytokine. 2012;59(1):41–8.

Sonomoto K, Yamaoka K, Oshita K, et al. Interleukin-1beta induces differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells into osteoblasts via the Wnt-5a/receptor tyrosine kinase-like orphan receptor 2 pathway. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(10):3355–63.

Raggatt LJ, Qin L, Tamasi J, et al. Interleukin-18 is regulated by parathyroid hormone and is required for its bone anabolic actions. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(11):6790–8.

Saleh H, Eeles D, Hodge JM, et al. Interleukin-33, a target of parathyroid hormone and oncostatin m, increases osteoblastic matrix mineral deposition and inhibits osteoclast formation in vitro. Endocrinology. 2011;152(5):1911–22.

Rifas L. T-cell cytokine induction of BMP-2 regulates human mesenchymal stromal cell differentiation and mineralization. J Cell Biochem. 2006;98(4):706–14.

Pacifici R. The immune system and bone. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2010;503(1):41–53.

Pacifici R. T cells: critical bone regulators in health and disease. Bone. 2010;47(3):461–71.

Nicolaidou V, Wong MM, Redpath AN, et al. Monocytes induce STAT3 activation in human mesenchymal stem cells to promote osteoblast formation. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e39871.

Hermann KG, Baraliakos X, van der Heijde DM, et al. Descriptions of spinal MRI lesions and definition of a positive MRI of the spine in axial spondyloarthritis: a consensual approach by the ASAS/OMERACT MRI study group. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(8):1278–88

Bollow M, Fischer T, Reisshauer H, et al. Quantitative analyses of sacroiliac biopsies in spondyloarthropathies: T cells and macrophages predominate in early and active sacroiliitis- cellularity correlates with the degree of enhancement detected by magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Rheum Dis. 2000;59(2):135–40.

Appel H, Kuhne M, Spiekermann S, et al. Immunohistologic analysis of zygapophyseal joints in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(9):2845–51.

Appel H, Loddenkemper C, Grozdanovic Z, et al. Correlation of histopathological findings and magnetic resonance imaging in the spine of patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8(5):R143.

Baraliakos X, Listing J, Brandt J, et al. Radiographic progression in patients with ankylosing spondylitis after 4 yrs of treatment with the anti-TNF-alpha antibody infliximab. Rheumatol (Oxford). 2007;46(9):1450–3.

Baraliakos X, Listing J, Rudwaleit M, et al. The relationship between inflammation and new bone formation in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2008;10(5):R104.

van der Heijde D, Landewe R, Baraliakos X, et al. Radiographic findings following two years of infliximab therapy in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(10):3063–70.

van der Heijde D, Landewe R, Einstein S, et al. Radiographic progression of ankylosing spondylitis after up to two years of treatment with etanercept. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(5):1324–31.

Maksymowych WP, Chiowchanwisawakit P, Clare T, et al. Inflammatory lesions of the spine on magnetic resonance imaging predict the development of new syndesmophytes in ankylosing spondylitis: evidence of a relationship between inflammation and new bone formation. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(1):93–102.

Pedersen SJ, Chiowchanwisawakit P, Lambert RG, et al. Resolution of inflammation following treatment of ankylosing spondylitis is associated with new bone formation. J Rheumatol. 2011;38(7):1349–54.

Pedersen SJ, Sorensen IJ, Lambert RG, et al. Radiographic progression is associated with resolution of systemic inflammation in patients with axial spondylarthritis treated with tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitors: a study of radiographic progression, inflammation on magnetic resonance imaging, and circulating biomarkers of inflammation, angiogenesis, and cartilage and bone turnover. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(12):3789–800.

• Baraliakos X, Haibel H, Listing J, et al. Continuous long-term anti-TNF therapy does not lead to an increase in the rate of new bone formation over 8 years in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202698. Long-term follow-up of patients treated with anti-TNF therapy; effects on syndesmophyte formation.

Ralston SH, Urquhart GD, Brzeski M, et al. Prevalence of vertebral compression fractures due to osteoporosis in ankylosing spondylitis. BMJ. 1990;300(6724):563–5.

Klingberg E, Geijer M, Gothlin J, et al. Vertebral fractures in ankylosing spondylitis are associated with lower bone mineral density in both central and peripheral skeleton. J Rheumatol. 2012;39(10):1987–95.

Spencer DG, Park WM, Dick HM, et al. Radiological manifestations in 200 patients with ankylosing spondylitis: correlation with clinical features and HLA B27. J Rheumatol. 1979;6(3):305–15.

Frediani B, Allegri A, Falsetti P, et al. Bone mineral density in patients with psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2001;28(1):138–43.

Will R, Bhalla A, Palmer R, et al. Osteoporosis in early ankylosing spondylitis; a primary pathological event? Lancet. 1989;23:1483–5.

Marzo-Ortega H, McGonagle D, Haugeberg G, et al. Bone mineral density improvement in spondyloarthropathy after treatment with etanercept. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62(10):1020–1.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Conflict of Interest

Steven R. Goldring has served as a consultant for Bone Therapeutics, Pfizer, and Fidia and has received grant support from Boehringer Ingelheim.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Seronegative Arthritis

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Goldring, S.R. Osteoimmunology and Bone Homeostasis: Relevance to Spondyloarthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep 15, 342 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11926-013-0342-2

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11926-013-0342-2