Abstract

Purpose

Increased type I interferon is considered relevant to the pathology of a number of monogenic and complex disorders spanning pediatric rheumatology, neurology, and dermatology. However, no test exists in routine clinical practice to identify enhanced interferon signaling, thus limiting the ability to diagnose and monitor treatment of these diseases. Here, we set out to investigate the use of an assay measuring the expression of a panel of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) in children affected by a range of inflammatory diseases.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A cohort study was conducted between 2011 and 2016 at the University of Manchester, UK, and the Institut Imagine, Paris, France. RNA PAXgene blood samples and clinical data were collected from controls and symptomatic patients with a genetically confirmed or clinically well-defined inflammatory phenotype. The expression of six ISGs was measured by quantitative polymerase chain reaction, and the median fold change was used to calculate an interferon score (IS) for each subject compared to a previously derived panel of 29 controls (where +2 SD of the control data, an IS of >2.466, is considered as abnormal). Results were correlated with genetic and clinical data.

Results

Nine hundred ninety-two samples were analyzed from 630 individuals comprising symptomatic patients across 24 inflammatory genotypes/phenotypes, unaffected heterozygous carriers, and controls. A consistent upregulation of ISG expression was seen in 13 monogenic conditions (455 samples, 265 patients; median IS 10.73, interquartile range (IQR) 5.90–18.41), juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus (78 samples, 55 patients; median IS 10.60, IQR 3.99–17.27), and juvenile dermatomyositis (101 samples, 59 patients; median IS 9.02, IQR 2.51–21.73) compared to controls (78 samples, 65 subjects; median IS 0.688, IQR 0.427–1.196), heterozygous mutation carriers (89 samples, 76 subjects; median IS 0.862, IQR 0.493–1.942), and individuals with non-molecularly defined autoinflammation (89 samples, 69 patients; median IS 1.07, IQR 0.491–3.74).

Conclusions and Relevance

An assessment of six ISGs can be used to define a spectrum of inflammatory diseases related to enhanced type I interferon signaling. If future studies demonstrate that the IS is a reactive biomarker, this measure may prove useful both in the diagnosis and the assessment of treatment efficacy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Given their potent and broad effects, the type I interferons represent both key molecules in anti-viral defense and potential mediators of inflammatory disease. As such, the induction, transmission, and resolution of the interferon response are tightly regulated. Mendelian disorders associated with a persistent upregulation of type I interferons, the so-called type I interferonopathies, and related non-monogenic phenotypes, most particularly systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and dermatomyositis (DM), represent examples of a disturbance of the homeostatic control of this complex system [1–4]. The recognition of these disorders will become of increasing clinical importance as “anti-interferon” treatments are developed [5].

Surprisingly, no routine laboratory test exists in current medical practice for the assessment of type I interferon signaling. Although a cytopathic protection assay, measuring anti-viral activity in patient material, was central in defining the first described monogenic type I interferonopathy, Aicardi-Goutières syndrome (AGS), this assay is neither widely available nor easily automated [6, 7]. Furthermore, type I interferon mRNA and protein assays in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) have proven insensitive as disease biomarkers, leading to the development of a variety of proxy assays [8–12]. Such low levels of circulating type I interferons presumably reflect their high biological potency, with most cells expressing a type I interferon receptor.

Based on the initial work of others on SLE [13, 14], we previously defined the characteristics of a test involving quantitative PCR (qPCR) assessment of six interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) using RNA extracted from PBMCs of patients with AGS [15]. Here, we now report the use of this interferon signature in a large cohort of patients and controls screened for type I interferon signaling status. These data allow for a better understanding of the practical application, interpretation, and utility of such an assay, as well as an improved characterization of the relationship of distinct diseases to type I interferon and the core clinical features that should alert a physician to the possibility of a type I interferon-related disorder.

Methods

Patient Cohort

We tested patients, and in certain cases parents and siblings to these patients, referred to us for assessment of type I interferon status. Clinical and molecular data were evaluated through direct contact and/or collected via collaborating physicians. We included cases with molecularly confirmed monogenic inflammatory diseases and a number of patients with non-molecularly defined clinical phenotypes which were either known to be, or we hypothesized might be, associated with increased type I interferon signaling. Control samples comprised an ethnically diverse group of individuals who self-reported not to have any medical condition. We also included in our control group parents or siblings to a person with an autosomal dominant interferonopathy where the parent/sibling was negative for the familial mutation. Neither patients nor controls demonstrated features of infection at the time of sampling.

Interferon Score (IS)

Blood was collected into PAXgene tubes (PreAnalytix) and, after being kept at room temperature for between 1 and 72 h, was frozen at −20 °C until extraction. Total RNA was extracted from whole blood using a PAXgene (PreAnalytix) RNA isolation kit. RNA concentration was assessed using a spectrophotometer (FLUOstar Omega, Labtech). Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) analysis was performed using the TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) and cDNA derived from 40 ng total RNA. Using TaqMan probes for IFI27 (Hs01086370_m1), IFI44L (Hs00199115_m1), IFIT1 (Hs00356631_g1), ISG15 (Hs00192713_m1), RSAD2 (Hs01057264_m1), and SIGLEC1 (Hs00988063_m1), the relative abundance of each target transcript was normalized to the expression level of HPRT1 (Hs03929096_g1) and 18S (Hs999999001_s1) and assessed with the Applied Biosystems StepOne Software v2.1 and DataAssist Software v.3.01. For each of the six probes, individual (patient and control) data were expressed relative to a single calibrator (control C25) (Table S1). The median fold change of the six ISGs, when compared to the median of previously collected 29 healthy controls, was used to create an IS for each individual. Relative quantification (RQ) is equal to 2−ΔΔCt, i.e., the normalized fold change relative to the control data. In this way, we define an abnormal IS as being greater than +2 standard deviations above the mean of this control group, i.e., 2.466.

Statistics

In the absence of a normal distribution, ISG levels and ISs were log-transformed and analyzed with parametric testing (t tests for two groups, one-way ANOVA for more than two groups). Tests for multiple comparisons, Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test or Dunnett’s multiple comparison test as appropriate, were applied as detailed in the figure legends. GraphPad Prism version 6 for Mac OS X was used for statistical analysis.

Ethics Approvals

The study was approved by the Leeds (East) Research Ethics Committee (reference number 10/H1307/132) and by the Comité de Protection des Personnes (ID-RCB/EUDRACT: 2014-A01017-40).

Results

Overall Cohort Characteristics

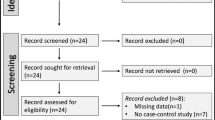

Over a period of 6 years, we tested a total of 2181 samples for an interferon signature. These samples were from 1565 individuals, comprising 75 persons considered as controls (96 samples); 1264 patients (1827 samples); and 209 parents (241 samples) and 17 siblings (17 samples) of affected patients (Fig. 1).

Flow chart showing inclusion/exclusion criteria for study participation. The number of measurements (samples) is given, together with the number of individuals/number of families below/in brackets. Treatment* refers to samples excluded (n = 93) because patients were on reverse transcriptase or JAK inhibitors

We excluded the following from this total of 2181 samples: 187 samples from controls, parents, and siblings where data on age, sex, or genotype were unavailable or where a proband was also excluded (see below); 42 samples from 12 AGS patients under treatment with reverse transcriptase inhibitors (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02363452?term=Aicardi+Goutieres&rank=1); 51 samples from seven IFIH1- and TMEM173-mutated patients under treatment with the JAK1/2 inhibitor ruxolitinib [5]; 175, seven, and 13 results from 161, seven, and 10 individuals with, respectively, adult-onset SLE/mixed connective tissue disease, retinal vasculopathy and cerebral leukodystrophy (RVCL), and STAT1 gain-of-function mutations which were performed as part of separate studies. We also excluded 714 samples from 597 patients where there was no genetic diagnosis and/or where phenotypic data were limited/allowed for no definite clinical diagnosis, there was no family history of similarly affected relatives, and for whom we had tested less than three ISs.

Following the above exclusions, our cohort consisted of 992 samples from 630 individuals, specifically: 78 samples from 65 controls (including 31 parents and seven siblings to patients with a molecularly proven autosomal dominant type I interferonopathy, most particularly due to heterozygous mutations in TREX1, ADAR1, IFIH1, and TMEM173, where the mutation was shown to have occurred de novo) (Table S1); 84 samples from 71 parents and five samples from five siblings where the parent/sibling of a person with biallelic mutations in a known type I interferonopathy-causing gene was shown to be heterozygous for one familial mutation (Table S2); and 825 samples from 489 patients which we divided into three groups for ease of analysis (Table 1). Group 1 comprises patients with one or more interferon signature reading(s) and a confirmed molecular diagnosis in any of the following 13 genes considered to have a proven link to type I interferon production/signaling: TREX1 (Table S3), RNASEH2A (Table S4), RNASEH2B (Table S5), RNASEH2C (Table S6), SAMHD1 (Table S7), ADAR1 (Table S8), IFIH1 (Table S9), ACP5 (Table S10), TMEM173 (Table S11), C1Q (Table S12), C2 (Table S12), ISG15 (Table S13), and SKIV2L (Table S14). Of note, we only included patients with biallelic mutations in these genes, except for those individuals with recognized dominant mutations in TREX1 (at positions p.Asp18 and p.Asp200), ADAR1 (at position p.Gly1007), IFIH1, and TMEM173. In group 2, we included patients with a confirmed molecular diagnosis of any other genotype, where at least one patient from each of at least two different families tested positive for an interferon signature on at least one occasion. This group thus comprised patients with mutations in DNASE1L3 (Table S15), PRKDC (Table S16), CECR1 (Table S17), RNASET2 (Table S18), and TRNT1 (Table S19). Finally, in group 3, we included patients with a clinical diagnosis of juvenile SLE (JSLE) (Table S20); juvenile DM (JDM) (Table S21); systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (sJIA) (Table S24) and other, non-systemic, JIA (pJIA) (Table S25); a molecularly undetermined phenotype which was clinically labeled as autoinflammatory (defined here as unexplained recurrent fevers and/or organ-specific features with elevated markers of systemic inflammation in the absence of autoimmunity and underlying infection) (Table S23); and patients with a phenotype variably comprising neurological, dermatological, rheumatological, and immunological features reminiscent of the known type I interferonopathy spectrum (Table S22), who screened negative for mutations in relevant type I interferonopathy-associated genes and who demonstrated a positive IS on three or more occasions or had a similarly affected relative with a minimum of three positive ISs shared between affected family members.

Results in Controls

Of 78 ISs from 65 controls, seven (9.0%) were abnormal (median IS 0.688, IQR 0.427–1.196) (Table 1, Table S1). In only two of these was the IS above five. The IS was measured on more than one occasion in 12 control individuals, with three persons being sampled three times. On 26 of 27 occasions, the IS was normal (Figure S1), the one positive sample returning an IS of 23.4 which was normal on repeat sampling. Controls ranged from 1 year to 93 years of age and there was no correlation between age and IS (p = NS). Thirty-five of 65 controls were female.

Results in Group 1

In this group, we measured 455 interferon signatures from 265 mutation-positive patients belonging to 222 families. All of these genotypes were associated with a significant upregulation of type I interferon signaling (median IS 10.73, IQR 5.90–18.41) (Table 1, Fig. 2a, Figure S2) compared to controls. Thirty-three of 148 samples (22.30%) from patients with mutations in RNASEH2B demonstrated a normal IS, and a lower median IS (6.10, IQR 2.74–10.84) was observed in this group compared to all other genotypes (median IS 13.14, IQR 8.12–21.54), with the next lowest median ISs associated with mutations in the two other proteins comprising the RNase H2 complex. A comparison of the median RQ value for each of the six individual ISGs across the genotypes comprising group 1 revealed higher fold induction of IFI27 and SIGLEC1 in patients mutated in ACP5, TMEM173, C1Q, and ISG15 compared to all other group 1 genotypes and to patients in group 3 (Fig. 3).

Interferon score plotted for each sample according to genotype/phenotype. a 455 group 1 patient samples. b 30 group 2 patient samples. c 340 group 3 patient samples. Black horizontal lines represent the median for each patient group. Interferon scores calculated from the median fold change in RQ (relative quantification) values of a panel of six interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs). Blue dots represent an interferon score of less than 2.466. Red dots represent an interferon score of greater than 2.466. Magenta dots represent patients treated with IL1 blockade. Analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test

Median fold expression of six interferon-stimulated genes according to genotype. Median relative quantification (RQ) value for each of six interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) measured in a 74 TREX1, 11 RNASEH2A, 115 RNASEH2B, 16 RNASEH2C, 45 SAMHD1, 52 ADAR1, and 59 IFIH1 samples with a positive (>2.466) interferon score; b 14 ACP5, 14 TMEM173, four C1QA, and five ISG15 samples with a positive (>2.466) interferon score; c 101 JDM, 21 sJIA, 58 autoinflammatory, 72 molecularly undefined interferonopathy, 78 JSLE, and ten pJIA. RQ is equal to 2−∆∆Ct, i.e., the normalized fold change relative to a control

Ten samples from patients mutated in TREX1 (two of 40 patients; three of 77 samples), ADAR1 (four of 34 individuals; four of 56 samples), and ACP5 (two of 12 patients; three of 17 samples) also returned normal results (Fig. 2a, Table S26), versus none of 95 patients (none of 157 samples) with the nine other genotypes. We note that some, but not all, of these interferon signature-negative patients demonstrated a milder clinical phenotype in comparison with other cases mutated in these same genes (data not shown). Of further note, one of the two patients with ACP5-related disease with a normal IS was on high-dose immunosuppressants and was reported to have responded well clinically at the time of sampling.

Results in Group 2

In this group, we measured 30 interferon signatures from 17 mutation-positive patients belonging to 14 families (Fig. 2b, Figure S3). For each of the five genotypes, CECR1 (11 samples, five patients), RNASET2 (six samples, five patients), PRKDC (six samples, two patients), TRNT1 (four samples, three patients), and DNASE1L3 (three samples, two patients), we recorded positive ISs in at least one patient from each of at least two different families (Fig. 2b).

Results in Group 3

Group 3 includes patients with molecularly undefined phenotypes, where we measured 340 interferon signatures from 207 patients belonging to 187 families (Fig. 2c, Figure S4). Our data mirror the results from multiple studies demonstrating an upregulation of interferon signaling in a significant proportion of individuals with JSLE and JDM, where 82% (64 of 78) and 75% (76 of 101) of samples were abnormal in these two phenotypic groupings, respectively (JSLE: median IS 10.60, IQR 3.99–17.27; JDM: median IS 9.02, IQR 2.51–21.73) (Table 1). We note that a number of these patients were under treatment, and some had clinically quiescent disease at the time of sampling. In contrast, a lower proportion (14 of 41) of patients with a clinical diagnosis of a non-molecularly determined autoinflammatory phenotype returned a positive IS (median 1.25, IQR 0.59–4.06). Considering another complex disease, sJIA, we identified five of 19 patients with a positive IS, 11 of whom were being treated with interleukin 1 (IL1) blockade. Finally, we also included in this group 72 samples from 24 patients belonging to 17 families who did not carry a mutation in known clinically relevant type I interferonopathy-associated genes and where we recorded an upregulation of type I interferon signaling measured on at least three occasions—thus, likely indicative of a true association with enhanced type I interferon signaling (median IS 9.38, IQR 6.67–13.98).

Results in Parents and Siblings of Patients in Group 1

The large majority of samples from proven heterozygous carrier parents (66 of 84 samples) and siblings (four of five samples) to patients with biallelic mutations in AGS1-7 and ACP5 did not demonstrate an interferon signature (median IS 0.862, IQR 0.493–1.942) (Figure S5). Ten of the 18 abnormal parental signatures were recorded in individuals heterozygous for a mutation in ADAR1.

Discussion

We present an overview of our experience of screening a large cohort of patients and controls for an induction of type I interferon signaling in whole blood by quantifying the expression of six ISGs—IFI27, IFI44L, IFIT1, ISG15, RSAD2, and SIGLEC1. There is no consensus as to the precise set of genes to measure when testing for an interferon signature. Nor is there a universally accepted method for calculating an IS based on a composite of multi-gene transcript upregulation. Prior to this study, we measured the expression of 15 ISGs in patients with mutations in ADAR1 [16]. Based on those results, and a series of unpublished genome-wide expression experiments, we then focused on six ISGs that were highly expressed in individuals from a cohort of molecularly defined AGS patients [15]. The median fold change of the six ISGs compared to the median of 29 healthy controls was used to create an IS for each patient, with a value greater than two standard deviations above the mean score of the controls (>2.466) being designated as positive. In this previously published work, we also showed that our IS positively correlated with an assay of anti-viral cytopathic protection.

The extended control data set presented here confirms that the large majority of healthy persons do not demonstrate an upregulation of type I interferon signaling, irrespective of age or sex. In contrast, work published by many groups has shown that enhanced type I interferon signaling is a reliable biomarker of a number of clinical phenotypes [13, 14, 17]. Given that our data recapitulate the results of these genome-wide expression studies, we consider that the simple screening assay presented here has validity as a tool that can differentiate patients from controls according to type I interferon status, frequently in the absence of any other indices of inflammation.

Although ISG transcripts can be induced by infection, effectively resulting in a “false positive” result in the situations under consideration here, our data show that the IS is reproducible and consistent over time in the large majority of cases. Thus, taking all individuals in whom we recorded more than one IS, repeat sampling in 91 of 108 patients with a monogenic interferonopathy was consistent for a positive/negative IS (with nine of the 17 patients demonstrating discordant results being mutated in RNASEH2B). Furthermore, in 19 patients mutated in any of AGS1-7 where we recorded four or more serial measurements, the scores were consistently positive in all cases—over periods spanning between 4 months and more than 3 years (Fig. 4). Indeed, we have shown previously that such repeat testing can enable the identification of new disease genes [18] and the definition of novel genotype-phenotype associations [19].

Interferon scores in patients where four or more serial samples were recorded. Data shown are interferon scores plotted against time (years) since first sampling. Interferon scores are calculated from the median fold change in relative quantification (RQ) values for a panel of six interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs). The blue dashed line represents the boundary of a positive/negative score (2.466). The number of serial samples for each patient is shown in brackets in the legend

Our group 1 comprises 13 genotypes in which a link to enhanced interferon signaling seems established—TREX1 [20], RNASEH2A, RNASEH2B, RNASEH2C [21], SAMHD1 [22], ADAR1 [16], IFIH1 [18], ACP5 [23, 24], TMEM173 [25], C1Q [26], C2, ISG15 [27], and SKIV2L [28]. Although we group these genotypes for ease of analysis, it is interesting that a comparison of the median RQ value for each of the six individual ISGs revealed markedly higher fold induction of IFI27 and SIGLEC1 in patients mutated in ACP5, TMEM173, C1Q, and ISG15 compared to all other group 1 genotypes and to patients in group 3 (Fig. 3). This observation suggests genotype-specific patterns of ISG induction which are worthy of further interrogation, using genome-wide expression arrays, in a larger number of patients. We point out here that our cohort does not represent a survey of all putative monogenic type I interferonopathies, since we have yet to assess any patients with mutations in PSMB8, PSMB4, PSMA3 [29], DDX58 [30], POLA1 [31], or USP18 [32] using our screening assay [33].

In group 1, we measured 455 interferon signatures from 265 mutation-positive patients, of which 412 samples (91%) were abnormal. Of the 43 data points falling within the normal range, 33 were from patients mutated in RNASEH2B (Fig. 2, Table S26). As such, a normal result does not rule out a diagnosis of these discrete monogenic interferonopathies. However, a positive IS is clearly a reliable disease biomarker and can serve as a useful diagnostic screening tool.

The rationale for our group 2 designation was to try to identify further monogenic diseases demonstrating a consistent association with upregulated type I interferon signaling, where there is currently no biological evidence for such a link. For inclusion in this group, we required that at least one patient from each of at least two different families with the same monogenic disease demonstrated an upregulation of type I interferon signaling on at least one occasion. This allowed us to suggest that there might be a positive correlation of interferon induction with mutations in CECR1 [34, 35], RNASET2 [36, 37], PRKDC [38], TRNT1 [39], and DNASE1L3 [40, 41]. However, the small number of patients from whom we received repeat samples means that these putative associations need to be evaluated in larger cohorts of patients.

Mutations in the genes included in our group 1 can be associated with a remarkably broad spectrum of discrete or combined neurological, rheumatological, and dermatological presentations. Informed by these data, we identified a group of 24 patients from 17 families demonstrating a consistent upregulation of type I interferon signaling (median IS 9.38, IQR 6.67–13.98), all of whom tested negative for known clinically relevant type I interferonopathy-associated genes. Considering the occurrence of affected siblings in four of these families, there is a high likelihood that certain of these patients have a currently undefined genetic basis to their disease. Important clinical indicators that should prompt consideration of this type I interferonopathy grouping include vasculitic skin lesions, intracranial calcification, spasticity, dystonia, glaucoma, recurrent fevers, interstitial lung disease, and lupus-like disease.

We did not collect enough samples from any monogenic entities to make a definitive statement on a null relationship to type I upregulation. However, we did test a group of 41 patients clinically defined as having autoinflammatory disease, the majority of whom (27 of 41) showed no evidence of enhanced type I interferon signaling at any time (median IS 1.25, IQR 0.59–4.06). These data lend support to the specificity of type I interferon-induced gene transcript measurement as a screening tool and lead us to suggest that autoinflammation can be both interferon (e.g., due to mutations in IFIH1 and TMEM173) and non-interferon related. Indeed, the only child included in our autoinflammatory group with a convincing upregulation of interferon signaling on multiple occasions (Table S23, AGS818) demonstrated recurrent chilblain-like lesions highly evocative of other type I interferonopathies.

While most patients with AGS are not currently treated by immunosuppression, a limitation of our study is that a majority of patients in groups 2 and 3 were receiving such therapy (details of which, where available, are given in S20, S21, S23, S24, and S25) when tested for an interferon signature. The possibility that such immunosuppression might attenuate a disease-associated upregulation of type I interferon signaling has been alluded to above. However, it is of note that many patients with JSLE and JDM demonstrated persistent upregulation of interferon signaling despite treatment. Interestingly, although sJIA is not normally associated with a type I interferon signature [42], we observed an upregulation of ISG expression in a small number of cases treated with IL1 blockers. This finding is concordant with a previous description of the induction of an interferon signature in JIA patients treated with anakinra and likely reflects currently undefined feedback loops triggered by these anti-cytokine agents [43]. As evidenced by the risk of developing interferon-driven pathology in the context of TNF-α blockade [44], such changes can be of clinical importance.

Summarizing, taken in clinical context, testing for an interferon signature represents a reliable screening tool for the identification of a variety of distinct genotypes and phenotypes. Such testing will likely become of high importance as therapies based on blocking interferon signaling become available [5, 45]. The interferon assay that we describe is practical, with the PAXgene system being stable for at least 72 h at room temperature, thus allowing for the easy transfer of samples to a reporting laboratory. At the same time, the IS represents a proxy assay, i.e., it does not directly measure the relevant disease-inducing molecule(s). Thus, we await the introduction of high-sensitivity assays of interferon protein which will be usefully combined with measures of ISG production as described here, thereby capturing the relationship between the inducing signal and the response to that signal.

References

Crow YJ. Type I, interferonopathies: a novel set of inborn errors of immunity. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1238:91–8.

Crow YJ, Manel N. Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome and the type I interferonopathies. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15(7):429–40.

Banchereau R, Hong S, Cantarel B, et al. Personalized immunomonitoring uncovers molecular networks that stratify lupus patients. Cell. 2016;165(6):1548–50.

Greenberg SA, Pinkus JL, Pinkus GS, et al. Interferon-alpha/beta-mediated innate immune mechanisms in dermatomyositis. Ann Neurol. 2005;57(5):664–78.

Frémond ML, Rodero MP, Jeremiah N, et al. Efficacy of the Janus Kinase 1/2 Inhibitor Ruxolitinib in the Treatment of Vasculopathy Associated with TMEM173-Activating Mutations in three children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016.

Goutieres F, Aicardi J, Barth PG, Lebon P. Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome: an update and results of interferon-alpha studies. Ann Neurol. 1998;44(6):900–7.

Lebon P, Meritet JF, Krivine A, Rozenberg F. Interferon and Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2002;6(Suppl A):A47–53. discussion A55-48, A77-86.

Hua J, Kirou K, Lee C, Crow MK. Functional assay of type I interferon in systemic lupus erythematosus plasma and association with anti-RNA binding protein autoantibodies. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(6):1906–16.

Niewold TB, Kariuki SN, Morgan GA, Shrestha S, Pachman LM. Elevated serum interferon-alpha activity in juvenile dermatomyositis: associations with disease activity at diagnosis and after thirty-six months of therapy. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(6):1815–24.

Seo YJ, Kim GH, Kwak HJ, et al. Validation of a HeLa Mx2/Luc reporter cell line for the quantification of human type I interferons. Pharmacology. 2009;84(3):135–44.

Li Y, Lee PY, Kellner ES, et al. Monocyte surface expression of Fcgamma receptor RI (CD64), a biomarker reflecting type-I interferon levels in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12(3):R90.

Berger Rentsch M, Zimmer G. A vesicular stomatitis virus replicon-based bioassay for the rapid and sensitive determination of multi-species type I interferon. PLoS One. 2011;6(10), e25858.

Bennett L, Palucka AK, Arce E, et al. Interferon and granulopoiesis signatures in systemic lupus erythematosus blood. J Exp Med. 2003;197(6):711–23.

Baechler EC, Batliwalla FM, Karypis G, et al. Interferon-inducible gene expression signature in peripheral blood cells of patients with severe lupus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(5):2610–5.

Rice GI, Forte GM, Szynkiewicz M, et al. Assessment of interferon-related biomarkers in Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome associated with mutations in TREX1, RNASEH2A, RNASEH2B, RNASEH2C, SAMHD1, and ADAR: a case–control study. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(12):1159–69.

Rice GI, Kasher PR, Forte GM, et al. Mutations in ADAR1 cause Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome associated with a type I interferon signature. Nat Genet. 2012;44(11):1243–8.

Baechler EC, Bauer JW, Slattery CA, et al. An interferon signature in the peripheral blood of dermatomyositis patients is associated with disease activity. Mol Med. 2007;13(1–2):59–68.

Rice GI, Del Toro DY, Jenkinson EM, et al. Gain-of-function mutations in IFIH1 cause a spectrum of human disease phenotypes associated with upregulated type I interferon signaling. Nat Genet. 2014;46(5):503–9.

Livingston JH, Lin JP, Dale RC, et al. A type I interferon signature identifies bilateral striatal necrosis due to mutations in ADAR1. J Med Genet. 2014;51(2):76–82.

Crow YJ, Hayward BE, Parmar R, et al. Mutations in the gene encoding the 3′-5′ DNA exonuclease TREX1 cause Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome at the AGS1 locus. Nat Genet. 2006;38(8):917–20.

Crow YJ, Leitch A, Hayward BE, et al. Mutations in genes encoding ribonuclease H2 subunits cause Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome and mimic congenital viral brain infection. Nat Genet. 2006;38(8):910–6.

Rice GI, Bond J, Asipu A, et al. Mutations involved in Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome implicate SAMHD1 as regulator of the innate immune response. Nat Genet. 2009;41(7):829–32.

Briggs TA, Rice GI, Daly S, et al. Tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase deficiency causes a bone dysplasia with autoimmunity and a type I interferon expression signature. Nat Genet. 2011;43(2):127–31.

Lausch E, Janecke A, Bros M, et al. Genetic deficiency of tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase associated with skeletal dysplasia, cerebral calcifications and autoimmunity. Nat Genet. 2011;43(2):132–7.

Liu Y, Jesus AA, Marrero B, et al. Activated STING in a vascular and pulmonary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(6):507–18.

Santer DM, Hall BE, George TC, et al. C1q deficiency leads to the defective suppression of IFN-alpha in response to nucleoprotein containing immune complexes. J Immunol. 2010;185(8):4738–49.

Zhang X, Bogunovic D, Payelle-Brogard B, et al. Human intracellular ISG15 prevents interferon-alpha/beta over-amplification and auto-inflammation. Nature. 2015;517(7532):89–93.

Eckard SC, Rice GI, Fabre A, et al. The SKIV2L RNA exosome limits activation of the RIG-I-like receptors. Nat Immunol. 2014;15(9):839–45.

Brehm A, Liu Y, Sheikh A, et al. Additive loss-of-function proteasome subunit mutations in CANDLE/PRAAS patients promote type I IFN production. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(11):4196–211.

Jang MA, Kim EK, Now H, et al. Mutations in DDX58, which encodes RIG-I, cause atypical Singleton-Merten syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2015;96(2):266–74.

Starokadomskyy P, Gemelli T, Rios JJ, et al. DNA polymerase-alpha regulates the activation of type I interferons through cytosolic RNA:DNA synthesis. Nat Immunol. 2016;17(5):495–504.

Meuwissen ME, Schot R, Buta S, et al. Human USP18 deficiency underlies type 1 interferonopathy leading to severe pseudo-TORCH syndrome. J Exp Med. 2016;213(7):1163–74.

Rodero MP, Crow YJ. Type I interferon-mediated monogenic autoinflammation: the type I interferonopathies, a conceptual overview. J Exp Med. 2016;213(12):2527–38.

Zhou Q, Yang D, Ombrello AK, et al. Early-onset stroke and vasculopathy associated with mutations in ADA2. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(10):911–20.

Navon Elkan P, Pierce SB, Segel R, et al. Mutant adenosine deaminase 2 in a polyarteritis nodosa vasculopathy. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(10):921–31.

Henneke M, Diekmann S, Ohlenbusch A, et al. RNASET2-deficient cystic leukoencephalopathy resembles congenital cytomegalovirus brain infection. Nat Genet. 2009;41(7):773–5.

Tonduti D, Orcesi S, Jenkinson EM, et al. Clinical, radiological and possible pathological overlap of cystic leukoencephalopathy without megalencephaly and Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2016;20(4):604–10.

Mathieu AL, Verronese E, Rice GI, et al. PRKDC mutations associated with immunodeficiency, granuloma, and autoimmune regulator-dependent autoimmunity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135(6):1578–88. e1575.

Chakraborty PK, Schmitz-Abe K, Kennedy EK, et al. Mutations in TRNT1 cause congenital sideroblastic anemia with immunodeficiency, fevers, and developmental delay (SIFD). Blood. 2014;124(18):2867–71.

Al-Mayouf SM, Sunker A, Abdwani R, et al. Loss-of-function variant in DNASE1L3 causes a familial form of systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2011;43(12):1186–8.

Sisirak V, Sally B, D’Agati V, et al. Digestion of chromatin in apoptotic cell microparticles prevents autoimmunity. Cell. 2016;166(1):88–101.

Allantaz F, Chaussabel D, Stichweh D, et al. Blood leukocyte microarrays to diagnose systemic onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis and follow the response to IL-1 blockade. J Exp Med. 2007;204(9):2131–44.

Quartier P, Allantaz F, Cimaz R, et al. A multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial with the interleukin-1 receptor antagonist anakinra in patients with systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis (ANAJIS trial). Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(5):747–54.

Conrad CD, Domizio JD, Mylonas A, et al. Paradoxical psoriasis—unabated type I IFN production induced by TNF blockade. Cytokine. 2015;76:66–112.

Oon S, Wilson NJ, Wicks I. Targeted therapeutics in SLE: emerging strategies to modulate the interferon pathway. Clin Transl Immunol. 2016;5(5), e79.

Acknowledgements

YJC confirms that all co-authors had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The authors confirm the absence of any conflicts of interest or relevant financial concerns relating to this study. We are very grateful to the affected families for their involvement in our research and to all clinicians who contributed samples. We gratefully acknowledge the following physicians for their help in supplying samples and clinical data, and apologize in advance for any relevant omissions from this list: Dr GM Abdel-Salam M.D., Dr M Abinun M.D., Dr N Aladjidi M.D., Dr C Altuzarra M.D., Pr P Aubourg M.D., Dr N Baaloul M.D., Dr N Bahi-Buisson M.D., Dr E Baildam M.D., Dr C Barnerias M.D., Dr M Barth M.D., Dr R Battini M.D., Dr V Baudouin M.D., Dr N Bellon M.D., Dr G Bernard M.D., Dr D Bessis M.D., Dr O Boespflug Tanguy M.D., Dr A Burlina M.D., Dr A-C Burszteijn M.D., Dr C Cances M.D., Dr V Cantarin M.D., Dr A Carbasse M.D., Pr JL Casanova M.D., Dr M Castro-Gago M.D., Dr R Cimaz M.D., Pr B Chabrol M.D., Dr N Cordeiro M.D., Pr R Dale M.D., Dr N Darin M.D., Dr L De Waele M.D., Dr R Debre M.D., Pr I Desguerre M.D., Dr D Doummar M.D., Dr F Dubois-teklali M.D., Dr F Elmslie M.D., Dr M Fahey M.D., Dr P Fallon M.D., Dr A Faye M.D., Pr E Fazzi M.D., Dr M Frydman M.D., Dr M Gattorno M.D., Dr A Guven M.D., Dr B Heron-Longe M.D., Pr A Hovnanian M.D., Dr M Hully M.D., Pr T Kuijpers M.D., Dr R Kumar M.D., Dr M Kurian M.D., Dr V Laugel M.D., Dr D Lev M.D., Dr M Lim M.D., Dr JP Lin M.D., Dr J Livingston M.D., Dr B Lyons M.D., Dr S Mar M.D., Dr C Marques Lourenço M.D., Dr L Martorell M.D., Dr G McCullagh M.D., Dr L Mewasingh M.D., Dr P Meyer M.D., Dr I Meyts M.D., Dr C Mignot M.D., Dr I Moroni M.D., Dr J Munoz M.D., Dr R Nathan M.D., Dr V Navarro M.D., Dr L Norton M.D., Dr S Orcesci M.D., Dr E O’Toole M.D., Dr B Pérez Dueñas M.D., Dr U Peters M.D., Dr F Petit M.D., Dr A Phan M.D., Dr P Picco M.D., Dr M Rasmussen M.D., Dr M Rio M.D., Dr F Rivier M.D., Dr D Rodriguez M.D., Dr E Rosser M.D., Dr A Roubertie M.D., Dr S Scholl-Bürgi M.D., Dr K Schwarzenberger M.D., Dr C Scott M.D., Dr R Scott M.D., Pr E Sheridan M.D., Dr D Soler M.D., Dr S Sahlev M.D., Dr K Swoboda M.D., Dr J te Water Naude M.D., Dr D Tonduti M.D., Pr A Toutain M.D., Dr F Uettwiller M.D., Dr A Vanderver M.D., Dr N Van der Aa M.D., Dr M Vivarelli M.D., Dr J Vogt M.D., Dr J Walsh M.D., Dr E Wassmer M.D., Dr K Webb M.D., Dr MAAP Willemsen M.D., Dr C Wouters M.D., and Dr M Zaki M.D. YJC acknowledges funding from the European Research Council (GA 309449: Fellowship to Y.J.C), ERA-NET Neuron (MR/M501803/1), and a state subsidy managed by the National Research Agency (France) under the “Investments for the Future” (ANR-10-IAHU-01). IM acknowledges the Programme Santé-Sciences MD/PhD of the Institute Imagine, Paris. M.-L.F is supported by the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (Grant number 000427993). TAB acknowledges funding from the National Institute for Health Research, the Academy of Medical Sciences, the Wellcome Trust, Medical Research Council, British Heart Foundation, Arthritis Research UK, Prostate Cancer UK, and the Royal College of Physicians.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(DOCX 1678 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Rice, G.I., Melki, I., Frémond, ML. et al. Assessment of Type I Interferon Signaling in Pediatric Inflammatory Disease. J Clin Immunol 37, 123–132 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10875-016-0359-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10875-016-0359-1