-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

A. Hočevar, A. Ambrožič, B. Rozman, T. Kveder, M. Tomšič, Ultrasonographic changes of major salivary glands in primary Sjögren's syndrome. Diagnostic value of a novel scoring system, Rheumatology, Volume 44, Issue 6, June 2005, Pages 768–772, https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keh588

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Objectives. To reveal typical ultrasonographic (US) changes in major salivary glands associated with Sjögren's syndrome (SS) and to determine the diagnostic value of a novel US scoring system.

Methods. In 218 consecutive patients with suspected SS, US of both parotid and submandibular salivary glands was performed besides the regular diagnostic procedure following the American–European Consensus Group criteria of 2002. Five US parameters were assessed: echogenicity, inhomogeneity, number of hypoechogenic areas, the hyperechogenic reflections and clearness of the borders of the salivary gland. The grades of these five parameters for all four salivary glands were summed. The final US score ranged from 0 to 48.

Results. SS was established in 68 patients. The remaining 150 subjects, in whom SS was not confirmed, constituted our control group. All five US parameters were significantly associated with SS. The patients with SS had significantly higher US scores than those not diagnosed with SS (P<0.01). Setting the cut-off US score at 17 resulted in the best ratio of specificity (98.7%) to sensitivity (58.8%).

Conclusions. Well-defined US changes in the major salivary glands summarized in our novel scoring system were typical of SS patients. Advanced structural changes found on US imaging almost invariably represent SS salivary gland involvement.

Primary Sjögren's syndrome (SS) is the second most common chronic systemic autoimmune disease and is characterized by cellular and humoral autoimmune responses directed primarily against the exocrine glands [1]. The key clinical manifestation and the mainstay of the diagnosis of SS is dysfunction of the lachrymal and salivary glands, leading to symptoms and signs of keratoconjunctivitis sicca and xerostomia [2].

In the past three decades many sets of criteria for diagnosing SS have been proposed as a result of incomplete understanding of the aetiopathogenesis of the disease and the absence of a single, more specific test to form the basis of diagnosis [3]. In spite of recently published classification criteria proposed by the American–European Consensus group in 2002 (which also serve as diagnostic criteria) [4], the evaluation of salivary gland involvement in SS is still a matter of debate. In addition to standard tests for assessment of salivary gland involvement, namely the unstimulated salivary flow test, salivary gland scintigraphy and sialography, other methods have been studied (ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography) [5, 6]. Among them, ultrasonography (US) of the major salivary glands seems the most attractive as a non-invasive, inexpensive and non-irradiating investigation. However, only a few studies have evaluated the role of salivary gland US in diagnosing SS [7–14]. Comparison between them is rather difficult due to the different diagnostic criteria used. Since the publication of the new criteria set for SS only one study on the diagnostic value of salivary gland US has been reported [5].

The specific objectives of our cross-sectional study were to establish a practical method for evaluation of US changes of major salivary glands, combining previous findings and our own experience, and to determine the significance of US compared with formal classification criteria in the diagnosis of SS. The proposed semiquantitative scoring system summarizes all US changes of the major salivary glands that are typical of SS. US examination of salivary glands, as performed in our study, demonstrated very high specificity for SS and could provide important advances in SS diagnosis.

Subjects and methods

Subjects

We included 218 consecutive subjects (192 females and 26 males, mean age 51.5, range 23–84 yr) referred to the out-patient Department of Rheumatology, Medical Centre Ljubljana in the years 2002 and 2003 who were suspected of having SS. The suspicion was based on the patient's history, clinical or laboratory data. All subjects gave their informed consent. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Republic of Slovenia.

Clinical assessment

All patients were asked to come to our department between 9 and 11 a.m., having fasted and not brushed their teeth, rinsed their mouth, or smoked tobacco for at least 1 h before the examination. Six questions to assess both ocular and oral involvement were given to each patient. Information on comorbidities and related treatment was collected at the same time. Besides the questionnaire, all patients were subjected to a Schirmer-I test, unstimulated salivary flow test, rose Bengal score determination, and serological tests. If necessary, salivary scintigraphy and histopathological investigation of the minor salivary glands were carried out until four of the six American–European Consensus group classification criteria for SS [4] had been shown to be negative or until SS was diagnosed.

Serological tests

Antinuclear antibodies were assessed by indirect immunofluorescence on the Hep-2 cell line substrate (Immuno Concepts, USA). Anti-Ro/SS-A and anti-La/SS-B antibodies were tested by counter-immunoelectrophoresis [15].

Ultrasonography

US examination of the parotid and submandibular salivary glands was performed simultaneously with the SS diagnostic procedure. The observer who performed the US examination was unaware of the diagnosis. Greyscale images were obtained using an ATL HDI 3000 US scanner (Advanced Technologies Laboratories, Bothell, WA, USA) with a 5–12 MHz linear array transducer. Patients lay on their back and extended their necks on the side to be examined. Routine images of the salivary glands were obtained in longitudinal and transverse planes. The following US variables were investigated and the observed parameters were assessed semiquantitatively in both paired glands for each participant.

Parenchymal echogeneity was evaluated in comparison with the thyroid gland or when there was coincident thyroid gland disease by surrounding anatomical structures (muscular structures, subcutaneous fat). If the echogeneity was comparable to the thyroid, the grade was 0; if it was decreased, we graded it 1.

Homogeneity was graded from 0 to 3. Grading 0 was for a homogeneous gland, 1 for mild inhomogeneity, 2 for evident inhomogeneity, and 3 for a grossly inhomogeneous gland.

The presence of hypoechogenic areals was graded from 0 to 3 (grade 0, absent; grade 1, a few, scattered; grade 2, several; grade 3, numerous hypoechogenic areas).

Hyperechogenic reflections were graded from 0 to 3 in the parotid glands (grade 0, absent; grade 1, a few, scattered; grade 2, several; grade 3, numerous hyperechogenic reflections) and from 0 (absent) to 1 (present) in the submandibular glands.

Clearness of salivary gland borders was graded from 0 to 3 (grade 0, clear, regular defined borders; grade 1, partly defined borders; grade 2, ill-defined borders; grade 3, borders not visible).

Finally, the US score was calculated by summation of the grades for the five parameters described above for all four glands. US score ranged from 0 to 48.

Statistical analysis

For statistical comparisons, the t-test, the χ2 test and univariate or multivariate logistic regression analysis were employed. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Sixty-eight out of 218 subjects fulfilled the criteria for SS. The remaining 150 subjects, in whom SS was not confirmed, were our control group. There was no statistically significant difference between these two groups in the mean age, gender, use of anticholinergic drugs, smoking and in the frequency and duration of sicca symptoms.

On the other hand, the difference between the SS and non-SS group was statistically significant for objective features of dry eyes (P<0.01) and dry mouth (P = 0.01) and for the presence of anti-Ro and/or anti-La antibodies (P<0.0001) as well as in the number of positive minor salivary gland biopsy results (P<0.0001).

Ultrasonography

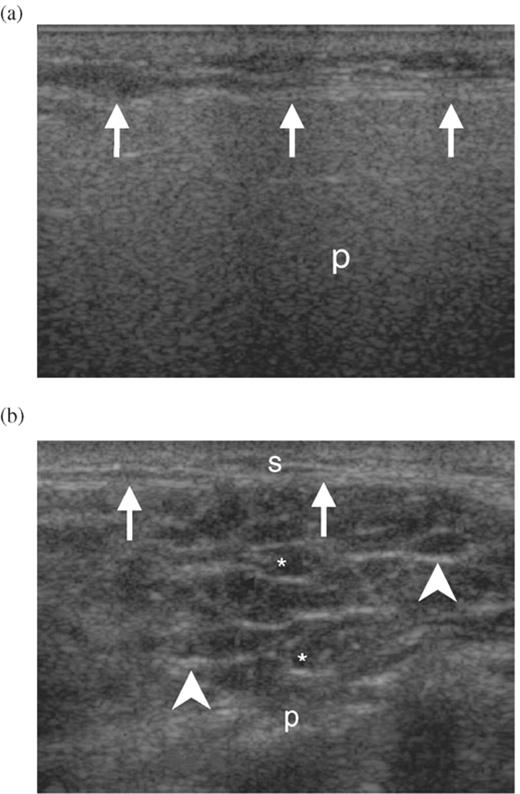

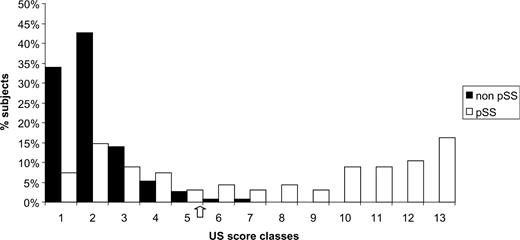

US visible structural changes were detected in 63/68 (92.6%) SS patients and in 99/150 (66.0%) subjects without confirmed SS (Fig. 1). The US score was calculated by summing the grades obtained for all four glands based on the assessment of the five observed parameters. Mean US score in SS patients was 24 (range from 0 to 48). Subjects without confirmed SS had the mean US score 3 (range from 0 to 21). US scores were then grouped into 13 classes. The percentage of subjects with and without SS with regard to the US score is shown in Fig. 2.

US images of a parotid gland. (a) Gland with normal structure. Arrows indicate parotid gland borders. (b) Gland with severe structural changes. Arrows indicate parotid gland borders; arrowheads indicate hyperechoic reflections; *hypoechoic areas. s, subcutaneus tissue; p, parotid gland.

Percentage of subjects with SS and without SS: US score grouped in 13 classes. Class 1 contains subjects with score 0; all other subjects, with score 1–48, were divided into 12 classes containing subjects with four consecutive scores. US score 17 is between classes 5 and 6.

Since mild changes of salivary glands (low US scores) were present in both groups, we set the cut-off US score as characteristic of SS (positive US result), at 17. Forty (58.8%) patients with SS and 2 (1.3%) non-SS subjects attained US score 17 or more (classes 6–13) as shown in Fig. 2.

Comparison of the clinical characteristics of SS patients with US scores ≥17 with those from patients with US scores less than 17 showed that patients with US score ≥17 were of similar mean age (51.8 vs 53.2 yr), gender (38 vs 25 females), and had a similar average duration (4.4 vs 2.7 yr) and frequency of sicca symptoms. There was also no statistically significant difference in the mean unstimulated salivary flow rate between SS patients with US score ≥17 and SS patients with US score <17 (0.7 vs 0.9 ml, respectively). However, the compared groups differed significantly in the mean number of positive dry eye tests (P<0.01), in the frequency and severity (according to Schall's criteria) of positive salivary gland scintigraphy (P<0.01), and in the prevalence anti-Ro and anti-La antibodies (P<0.01). Anti-La autoantibodies were detected only in the 12 patients from the group with US score ≥17. Although there was no significant difference in regard to the number of positive biopsy findings, the difference in the mean focus score reached statistical significance between the compared groups (P = 0.03).

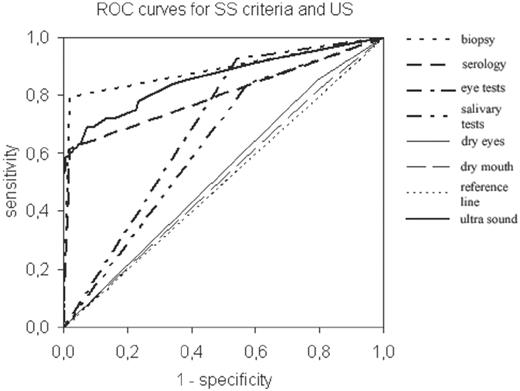

Finally, we compared the accuracy of different valid diagnostic tests in SS and salivary gland US. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were constructed by computing the sensitivity and specificity of different tests and their accuracy was measured by the area under the ROC curve. The calculated area under the salivary gland US ROC [0.86 ± 0.031; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.79–0.92] was intermediate between the biopsy ROC curve (0.89 ± 0.030; 95% CI 0.83–0.95) and the area of the immunoserological ROC curve (0.80 ± 0.038; 95% CI 0.72–0.87). The area of the dry eye test ROC curve (0.68 ± 0.037; 95% CI 0.61–0.75) and the area of the salivary gland dysfunction test ROC curve (0.63 ± 0.039; 95% CI 0.55–0.70) were much lower. The shape of the ROC curve for xerophthalmia and xerostomia was nearly the same as the reference curve's shape. Our findings are represented in Fig. 3.

Discussion

Nine different classification criteria sets have been suggested and used for the diagnosis of SS in the past three decades. They indicate that the diagnostic approach in SS is rather complicated and might be further improved. Since there is no single test with sufficient diagnostic value, the diagnosis of this chronic autoimmune disorder is at present established on the combination of characteristic signs and symptoms [3, 4]. In particular, the assessment of salivary gland manifestation is fairly complex. Currently accepted methods in the evaluation of xerostomia (salivary scintigraphy, parotid sialography and unstimulated salivary flow collection) have limited sensitivity and specificity (56.1% sensitivity and 80.7% specificity for the unstimulated salivary flow test and 87.2% sensitivity with 79.0% specificity for salivary gland scintigraphy) [16], and in some cases they cannot even be performed. Therefore newer procedures and imaging modalities for the demonstration of salivary gland involvement are being studied. One of them is salivary gland US. However, opinions are not completely uniform about the clinical usefulness of US examination in SS diagnostics [9, 17]. The majority of investigators reports parenchymal inhomogeneity of salivary glands with hypoechogenic areas as the most important sonographic sign in SS [8, 9], but there are differences in the reported diagnostic accuracy of salivary gland US changes. Some of these inconsistent results could be explained by the different SS classification criteria used, by the limited number of patients in studies performed, and by the US equipment employed (scanning transducers with different resolutions). Inadequate objectivity in evaluating pathological changes in sonographic images should be considered when assessing US images.

In the present study we aimed to establish a practical method for the evaluation of US changes of major salivary glands and to compare salivary gland US with currently accepted classification criteria for SS. Therefore we performed a US examination of the four major salivary glands in addition to diagnostic procedures in individuals whose history, clinical or laboratory findings suggested SS. Salivary glands in SS patients were significantly frequently hypoechogenic and inhomogeneous, and had unclear borders, hypoechogenic areas and hyperechogenic reflections significantly more commonly than glands of non-SS subjects. Comparison of US scores calculated from the constructed formula showed that the average US score in the SS patient group was 24 (range 0–48) and in the control group 3 (range 0–21). Considering the best sensitivity-to-specificity ratio, the cut-off point US score characteristic of SS was set at 17. Forty out of 68 subjects who fulfilled the last classifying criteria for SS [4] attained US score 17 or more. Using this cut-off point for the positive US test, the diagnostic sensitivity of salivary gland US in SS is 58.8%. The percentage is within the otherwise wide range of previous studies (from 33 to 90.9%) [6, 7]. Failure to detect changes in the remaining 28 SS patients may be due to the early stage of the disease or milder salivary gland involvement. Indeed, by comparing SS patients with US score <17 with patients with US score ≥17 we found a lower number of pathological ocular tests, milder salivary gland involvement assessed by salivary gland scintigraphy, a lower focus score on minor salivary gland biopsy and a lower prevalence of antinuclear, anti-Ro and anti-La autoantibodies in the former group of patients. In addition, autoantibodies against La antigen were detected only in patients’ sera from the group with US score ≥17. Similar results were reported by Makula [8]. In spite of an insignificant difference in average duration of sicca symptoms between our two compared groups of patients, mild US changes might in part be explained by shorter disease duration. Further follow-up of the patients is needed to verify this presumption.

The semiquantitative scoring system with the cut-off point 17 enables high specificity for SS diagnosis. Only two out of 150 subjects without confirmed SS attained a positive US score result. This gives high diagnostic specificity (98.7%).

By a close overview of data from two examined subjects without confirmed SS but with a US score indicating it, we found in both some elements of possible SS development. The first female participant had xerostomia, confirmed by pathological unstimulated salivary flow and scintigraphy and positive ocular tests. Autoantibodies against Ro and La antigens were not detected in her sera and changes found on the minor salivary gland biopsy did not fulfil the histological criteria (focus score 0.6). The second participant had, apart from subjective and objective dry eyes, a high focus score on the salivary gland biopsy (2.9), but was negative for other investigations.

ROC curves were employed to describe how well US examination and valid SS diagnostic tests can distinguish SS patients from controls without disease. A positive histopathological result was the best performer, followed by salivary gland US and immunoserological tests. The area under the ROC curve in all of these three investigations reached the range of good accuracy.

Finally, in clinical practice the predictive value is the most important measure of a test's performance. In the population we studied the positive predictive value for salivary gland US is 95.2% and the negative predictive value is 84.0%.

The subjective component of the salivary gland US assessment by only one observer was a major disadvantage of our study. To evaluate and minimize subjectivity of the US examination we had already performed another study with two blind investigators using the above-described semiquantitative scoring system, and compared their results. Good agreement was found between them (submitted for publication).

In conclusion, the salivary gland biopsy and immunoserological tests are the most noteworthy investigations in the present SS criteria [4]. We studied the value of US examination in diagnosing SS. In our opinion, the opportunity to perform US examination of major salivary glands at least represents another test of criterion no. 5: salivary gland involvement. On the other hand, the rather low sensitivity of salivary gland US does not make it appropriate for a screening test, since negative results do not exclude SS.

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest

References

Jonson R, Haga HJ, Gordon TP. Current concepts on diagnosis, autoantibodies and therapy in Sjoegren's syndrome.

Manthorpe R. New criteria for diagnosing Sjögren's syndrome: a step forward? —or …

Vitali C, Bombardieri S, Jonsson R et al. Classification criteria for Sjoegren's syndrome: a revised version of the European criteria proposed by the American–European Consensus group.

Niemelä RK, Takalo R, Pääkkö E et al. Ultrasonography of salivary glands in primary Sjögren's syndrome. A comparison with magnetic resonance imaging and magnetic resonance sialography of parotid glands.

Tonami H, Matoba M, Yokota H, Higashi K, Yamamoto I, Sugai S. CT and MR findings of bilateral lacrimal gland enlargement in Sjögren's syndrome.

DeVita S, Lorenzon G, Rossi G, Sabella M, Fossaluzza V. Salivary gland echography in primary and secondary Sjögren's syndrome.

Makula E, Pokorny G, Rajtar M, Kiss I, Kovacs A, Kovacs L. Parotid gland ultrasonography as a diagnostic tool in primary Sjögren's syndrome.

Salaffi F, Argalia G, Carotti M, Giannini FB, Palombi C. Salivary gland ultrasonography in the evaluation of primary Sjögren's syndrome. Comparison with minor salivary gland biopsy.

Yonetsu K, Takagi Y, Sumi M, Nakamura T. Sonography as a replacement for sialography for the diagnosis of salivary glands affected by Sjögren's syndrome.

Mandel L, Orchowski YS. Using ultrasonography to diagnose Sjögren's syndrome.

Ariji Y, Ohki M, Eguchi K et al. Texture analysis of sonographic features of the parotid gland in Sjögren's syndrome.

Takashima S, Morimoto S, Tomiyama N, Takeuchi N, Ikezoe J, Kozuka T. Sjögren syndrome: comparison of sialography and ultrasonography.

Bunn C, Kveder T. Counterimmunoelectrophoresis and immunodiffusion for the detection of antibodies to soluble cellular antigens. In: van Venrooij WJ, Maini RN, eds.

Vitali C, Moutsopoulos HM, Bombardieri S. The European Community Study group on diagnostic criteria for Sjögren syndrome. Sensitivity and specificity of tests for ocular and oral involvment in Sjögren syndrome.

Comments