-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

T. R. Mikuls, J. T. Farrar, W. B. Bilker, S. Fernandes, K. G. Saag, Suboptimal physician adherence to quality indicators for the management of gout and asymptomatic hyperuricaemia: results from the UK General Practice Research Database (GPRD), Rheumatology, Volume 44, Issue 8, August 2005, Pages 1038–1042, https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keh679

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Objectives: To examine adherence to validated quality indicators assessing the quality of allopurinol use in the treatment of gout and asymptomatic hyperuricaemia.

Methods. We determined physician adherence in the UK General Practice Research Database (GPRD) to three validated quality indicators developed to assess the quality of allopurinol prescribing practices. These indicators were developed to assess: (i) dosing in renal impairment; (ii) concomitant use with azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine; and (iii) use in the treatment of asymptomatic hyperuricaemia. We also examined the association of patient-level factors (sociodemographics, comorbidity, follow-up duration and concomitant medicine use) with the treatment of asymptomatic hyperuricaemia using multivariable logistic regression.

Results. Of the 63 105 gout patients, 185 (0.3%) were eligible for Quality Indicator 1 and 52 (0.1%) were eligible for Quality Indicator 2. There were an additional 471 patients with asymptomatic hyperuricaemia eligible for Quality Indicator 3. Rates of practice deviation for the three individual quality indicators ranged from 25 to 57%. Male sex, older age, a history of chronic renal failure, and a greater number of concomitant medications were significantly associated with increased odds of inappropriate treatment for asymptomatic hyperuricaemia. Hypertension and diuretic use were associated with lower odds of this practice.

Conclusions. One-quarter to one-half of all patients eligible for at least one of the validated quality of care indicators were subject to possible allopurinol prescribing error, suggesting that inappropriate prescribing practices are widespread with this agent. Future interventions aimed at reducing inappropriate allopurinol use are needed and should be targeted towards high-risk groups, including older men and those receiving multiple concomitant medications.

The xanthine oxidase inhibitor allopurinol is estimated to be used by over 1.2 million gout patients in the USA and UK alone [1]. Despite its frequent use, it appears that allopurinol is often prescribed inappropriately [2–5].

Investigations examining the quality of gout care have been relatively small and usually limited to the hospital setting [2–5]. To our knowledge, there have been no population-based studies examining either the frequency or determinants of medication error with the use of urate-lowering therapies. A major barrier to such research has been the lack of consensus regarding minimal standards of care in gout treatment. To address the lack of existing consensus in gout care, we recently developed quality of care indicators for gout management, using a previously validated expert panel process [6]. We examined physician adherence to urate-lowering therapy indicators using a national medical record database. The process indicators used in this study were developed to examine the quality of allopurinol prescribing practices in the following areas: (i) dosing with renal impairment; (ii) use with concomitant azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP); and (iii) use in the treatment of asymptomatic hyperuricaemia. We hypothesized that deviation from the quality indicators would be frequent and that adherence to the quality indicators would be lower for gout patients with evidence of comorbidity and polypharmacy.

Methods and materials

Quality indicator development

The methods of quality indicator development have been reported previously [6, 7]. These indicators represent minimal standards of care for gout management. Of the 10 quality indicators deemed to be valid by the two expert panels, seven assessed the use of urate-lowering therapies. Data were available to examine three of these validated quality indicators using the UK General Practice Research Database (GPRD). The quality indicators examined in this study are shown in Table 1.

Quality indicators in gout management specific to allopurinol use [6]

| Indicator number . | Quality indicator . |

|---|---|

| 1 | IF a gout patient is receiving an initial prescription for allopurinol AND has significant renal impairment (defined as a serum creatinine ≥2 mg/dl or measured/estimated creatinine clearance ≤50 ml/min) THEN the initial daily allopurinol dose should be less than 300 mg per day BECAUSE the risk of allopurinol-related toxicity is increased in the presence of significant renal impairment in gout patients given a daily allopurinol dose equal to or exceeding 300 mg. |

| 2 | IF a gout patient is given a prescription for xanthine oxidase inhibitor in the setting of required therapy with EITHER of the following medications: (1) azathioprine (Imuran) OR (2) 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP) THEN the dose of azathioprine/6-MP should be reduced by a minimum of 50% BECAUSE concurrent use of a xanthine oxidase inhibitor leads to a substantial increase in serum levels of azathioprine (and 6-MP) and increases the risk of severe drug-related myelosuppression. |

| 3 | IF a patient has asymptomatic hyperuricaemia characterized by (1) no prior history of gouty arthritis or tophaceous deposits AND (2) no prior history of nephrolithiasis or hyperuricosuria AND (3) no ongoing treatment of malignancy THEN urate-lowering therapies should NOT be initiated BECAUSE there is currently no widely accepted indication for the treatment of asymptomatic hyperuricaemia. |

| Indicator number . | Quality indicator . |

|---|---|

| 1 | IF a gout patient is receiving an initial prescription for allopurinol AND has significant renal impairment (defined as a serum creatinine ≥2 mg/dl or measured/estimated creatinine clearance ≤50 ml/min) THEN the initial daily allopurinol dose should be less than 300 mg per day BECAUSE the risk of allopurinol-related toxicity is increased in the presence of significant renal impairment in gout patients given a daily allopurinol dose equal to or exceeding 300 mg. |

| 2 | IF a gout patient is given a prescription for xanthine oxidase inhibitor in the setting of required therapy with EITHER of the following medications: (1) azathioprine (Imuran) OR (2) 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP) THEN the dose of azathioprine/6-MP should be reduced by a minimum of 50% BECAUSE concurrent use of a xanthine oxidase inhibitor leads to a substantial increase in serum levels of azathioprine (and 6-MP) and increases the risk of severe drug-related myelosuppression. |

| 3 | IF a patient has asymptomatic hyperuricaemia characterized by (1) no prior history of gouty arthritis or tophaceous deposits AND (2) no prior history of nephrolithiasis or hyperuricosuria AND (3) no ongoing treatment of malignancy THEN urate-lowering therapies should NOT be initiated BECAUSE there is currently no widely accepted indication for the treatment of asymptomatic hyperuricaemia. |

Quality indicators in gout management specific to allopurinol use [6]

| Indicator number . | Quality indicator . |

|---|---|

| 1 | IF a gout patient is receiving an initial prescription for allopurinol AND has significant renal impairment (defined as a serum creatinine ≥2 mg/dl or measured/estimated creatinine clearance ≤50 ml/min) THEN the initial daily allopurinol dose should be less than 300 mg per day BECAUSE the risk of allopurinol-related toxicity is increased in the presence of significant renal impairment in gout patients given a daily allopurinol dose equal to or exceeding 300 mg. |

| 2 | IF a gout patient is given a prescription for xanthine oxidase inhibitor in the setting of required therapy with EITHER of the following medications: (1) azathioprine (Imuran) OR (2) 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP) THEN the dose of azathioprine/6-MP should be reduced by a minimum of 50% BECAUSE concurrent use of a xanthine oxidase inhibitor leads to a substantial increase in serum levels of azathioprine (and 6-MP) and increases the risk of severe drug-related myelosuppression. |

| 3 | IF a patient has asymptomatic hyperuricaemia characterized by (1) no prior history of gouty arthritis or tophaceous deposits AND (2) no prior history of nephrolithiasis or hyperuricosuria AND (3) no ongoing treatment of malignancy THEN urate-lowering therapies should NOT be initiated BECAUSE there is currently no widely accepted indication for the treatment of asymptomatic hyperuricaemia. |

| Indicator number . | Quality indicator . |

|---|---|

| 1 | IF a gout patient is receiving an initial prescription for allopurinol AND has significant renal impairment (defined as a serum creatinine ≥2 mg/dl or measured/estimated creatinine clearance ≤50 ml/min) THEN the initial daily allopurinol dose should be less than 300 mg per day BECAUSE the risk of allopurinol-related toxicity is increased in the presence of significant renal impairment in gout patients given a daily allopurinol dose equal to or exceeding 300 mg. |

| 2 | IF a gout patient is given a prescription for xanthine oxidase inhibitor in the setting of required therapy with EITHER of the following medications: (1) azathioprine (Imuran) OR (2) 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP) THEN the dose of azathioprine/6-MP should be reduced by a minimum of 50% BECAUSE concurrent use of a xanthine oxidase inhibitor leads to a substantial increase in serum levels of azathioprine (and 6-MP) and increases the risk of severe drug-related myelosuppression. |

| 3 | IF a patient has asymptomatic hyperuricaemia characterized by (1) no prior history of gouty arthritis or tophaceous deposits AND (2) no prior history of nephrolithiasis or hyperuricosuria AND (3) no ongoing treatment of malignancy THEN urate-lowering therapies should NOT be initiated BECAUSE there is currently no widely accepted indication for the treatment of asymptomatic hyperuricaemia. |

Patients: the General Practice Research Database (GPRD)

The GPRD is a large population-based database that currently collects data from participating general practices, which together in 1999 provided primary health-care for over 1.8 million people in the UK (∼3% of the population). It contains computerized health data that was directly entered by participating general practitioners after a mandatory trial period of data entry to ensure the accuracy and completeness of the data [8]. Previous validation studies of the GPRD have shown the recording of pertinent clinical data to be highly accurate and nearly complete [9]. Clinical diagnoses were recorded using the Oxmis (Oxford Medical Information Systems) coding system [10].

All patients with a coded diagnosis of gout (or hyperuricaemia for Quality Indicator 3) between 1990 and 1999 were identified. The following patient characteristics were abstracted for each case: age, sex, the presence or absence of select comorbid conditions (coronary artery disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, nephrolithiasis, and chronic renal failure), follow-up duration, and concomitant medication use within the same calendar year (diuretics, cyclosporin, urate-lowering medicines, and total number of medications). Approval for this research was provided by the Office of National Statistics Scientific and Ethical Advisory Group and the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, the University of Pennsylvania, and the University of Nebraska.

Quality indicator eligibility

The methodology of Shekelle and colleagues [7] was used to construct the quality indicators using an IF–THEN–BECAUSE format [6] (Table 1): IF refers to the clinical characteristics that qualify individuals as eligible for the indicator; THEN indicates the actual process that should or should not be performed; and BECAUSE describes the anticipated health impact of the indicator.

We defined renal insufficiency (for Quality Indicator 1) using Oxmis diagnostic codes [10] for renal impairment/renal insufficiency, as laboratory results are not uniformly available in the GPRD. Diagnostic codes were reviewed separately by a board-certified nephrologist and a rheumatologist with an emphasis on specificity for significant and irreversible renal dysfunction. Diagnostic codes were rated as being indicative of ‘definite’, ‘probable’ or ‘possible’ chronic renal failure. Any disagreement was adjudicated by consensus. To enhance specificity, only ‘definite’ and ‘probable’ cases of chronic renal failure were examined.

Gout patients were eligible for Quality Indicator 2 if they had received azathioprine or 6-MP for at least 1 month before receiving a new prescription for allopurinol. In order to be classified as a new prescription, eligible patients were required to not have received allopurinol for at least the 6 previous months.

For Quality Indicator 3, we identified all GPRD patients with an Oxmis diagnostic code of hyperuricaemia, eliminating those patients with a history of gout (past or developing during follow-up) or past use of allopurinol, probenecid, colchicine, oral glucocorticoids, or indomethacin (medications indicative of a potential gout diagnosis). Based on the eligibility criteria for Quality Indicator 3 (Table 1), we also eliminated patients with a history of lymphoproliferative malignancy or nephrolithiasis (other possible indications for urate-lowering therapy).

Statistical analyses

For each quality indicator we compared patient factors (i.e. age, gender) among those prescribed allopurinol ‘correctly’ with those given the drug ‘incorrectly’. Categorical variables were examined using the χ2 statistic and continuous variables were compared using the Student's t-test. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to describe the association of select patient factors with inappropriate allopurinol use for Quality Indicator 3. Patient factors (sociodemographic factors, comorbidity and concomitant medicine use) were selected for inclusion in the model based on previous investigations [11, 12] suggesting associations with the occurrence of medication error. Provider factors for the GPRD generalists (i.e. age and training of physician) were not available in the data set. All analyses were adjusted for age and multivariable models were examined to adjust for potential confounding factors. All analyses were performed in SAS (SAS, Cary, NC, USA) and STATA (College Station, TX, USA).

Results

From 1990 to 1999, we identified 63 105 GPRD patients with a diagnosis of gout (data not shown). These patients were older (61±15 yr) and were predominantly men (78%). Gout patients had a mean follow-up duration in the database of 3.8±2.8 yr and, as anticipated, a significant proportion of patients had cardiovascular disease (26%), hypertension (25%) and diabetes (7%). Definite or probable chronic renal failure was noted in only 1.0% (n = 651) of gout patients. Approximately one-third of gout patients (34%) had received diuretic therapy during follow-up.

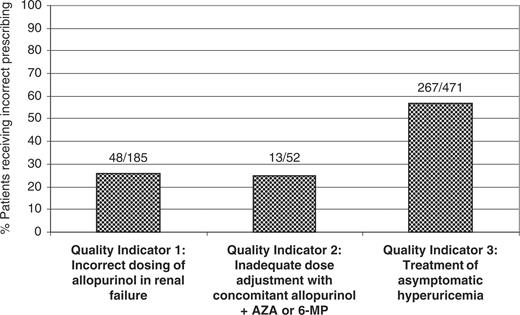

Of the 63 105 available gout patients, 185 (0.3%) were eligible to be in the denominator of Quality Indicator 1 and 52 (0.1%) were eligible for Quality Indicator 2. There were an additional 471 patients with asymptomatic hyperuricaemia eligible for Quality Indicator 3. Patients eligible for Quality Indicator 3 had a mean follow-up duration subsequent to their incident code for asymptomatic hyperuricaemia of almost 4 yr (Table 2). In addition, these patients had a mean observation period of 3 yr (2.9±2.6 and 3.3±2.5 for treated and untreated patients, respectively). Given the overlap between these patient groups (n = 11), there were 697 unique patients evaluable for the analyses. The frequency of potential prescribing error for each individual indicator is shown in Fig. 1. Rates of practice deviation for the three quality indicators ranged from 25 to 57%.

A comparison of patient characteristics of gout patients subject to allopurinol medication error vs subjects without error for each of the validated quality indicators: mean (±s.d.) or number (%)

| . | Quality Indicator 1: Dosing in context of renal failure (n = 185) . | . | Quality Indicator 2: Dose adjustment with concomitant use of allopurinol and azathioprine/6-MP (n = 52) . | . | Quality Indicator 3: Treatment of asymptomatic hyperuricaemia (n = 471) . | . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Error (n = 48) . | No error (n = 137) . | Error (n = 13) . | No error (n = 39) . | Error (n = 267) . | No error (n = 204) . | |||

| Sociodemographic | |||||||||

| Age: yr (s.d.) | 70.6 (14.8) | 70.5 (12.6) | 56.0 (9.1) | 55.7 (14.1) | 60.7 (15.7) | 58.0 (16.7) | |||

| Male sex (%) | 36 (75%) | 86 (63%) | 11 (85%) | 29 (75%) | 203 (76%) | 143 (70%) | |||

| Comorbidity | |||||||||

| Coronary artery disease (%) | 31 (65%) | 86 (63%) | 5 (39%) | 18 (46%) | 78 (29%)* | 42 (21%) | |||

| Hypertension (%) | 19 (40%)* | 78 (57%) | 8 (62%) | 26 (67%) | 74 (28%)* | 82 (40%) | |||

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 4 (8%) | 16 (12%) | 3 (23%) | 7 (18%) | 25 (9%) | 15 (7%) | |||

| Renal failure† (%) | – | – | 3 (23%) | 19 (49%) | 24 (9%)* | 4 (2%) | |||

| Concomitant drug use | |||||||||

| Diuretics (%) | 36 (75%) | 97 (71%) | 9 (69%) | 27 (69%) | 84 (32%) | 75 (37%) | |||

| Cyclosporin or FK-506 (%) | 2 (4%) | 10 (7%) | 12 (92%) | 25 (64%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.5%) | |||

| Total medications (s.d.) | 3.4 (2.3) | 3.8 (2.8) | 4.8 (3.0) | 3.8 (3.0) | 2.9 (2.2)* | 1.8 (2.2) | |||

| Follow-up duration (yr) | – | – | – | – | 3.8 (2.6) | 3.7 (2.4) | |||

| . | Quality Indicator 1: Dosing in context of renal failure (n = 185) . | . | Quality Indicator 2: Dose adjustment with concomitant use of allopurinol and azathioprine/6-MP (n = 52) . | . | Quality Indicator 3: Treatment of asymptomatic hyperuricaemia (n = 471) . | . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Error (n = 48) . | No error (n = 137) . | Error (n = 13) . | No error (n = 39) . | Error (n = 267) . | No error (n = 204) . | |||

| Sociodemographic | |||||||||

| Age: yr (s.d.) | 70.6 (14.8) | 70.5 (12.6) | 56.0 (9.1) | 55.7 (14.1) | 60.7 (15.7) | 58.0 (16.7) | |||

| Male sex (%) | 36 (75%) | 86 (63%) | 11 (85%) | 29 (75%) | 203 (76%) | 143 (70%) | |||

| Comorbidity | |||||||||

| Coronary artery disease (%) | 31 (65%) | 86 (63%) | 5 (39%) | 18 (46%) | 78 (29%)* | 42 (21%) | |||

| Hypertension (%) | 19 (40%)* | 78 (57%) | 8 (62%) | 26 (67%) | 74 (28%)* | 82 (40%) | |||

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 4 (8%) | 16 (12%) | 3 (23%) | 7 (18%) | 25 (9%) | 15 (7%) | |||

| Renal failure† (%) | – | – | 3 (23%) | 19 (49%) | 24 (9%)* | 4 (2%) | |||

| Concomitant drug use | |||||||||

| Diuretics (%) | 36 (75%) | 97 (71%) | 9 (69%) | 27 (69%) | 84 (32%) | 75 (37%) | |||

| Cyclosporin or FK-506 (%) | 2 (4%) | 10 (7%) | 12 (92%) | 25 (64%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.5%) | |||

| Total medications (s.d.) | 3.4 (2.3) | 3.8 (2.8) | 4.8 (3.0) | 3.8 (3.0) | 2.9 (2.2)* | 1.8 (2.2) | |||

| Follow-up duration (yr) | – | – | – | – | 3.8 (2.6) | 3.7 (2.4) | |||

6-MP, 6-mercaptopurine.

*P< 0.05 for difference in patient factor; patients with prescribing error vs those without error within quality indicator.

†Renal failure included definite and probable cases; not examined as determinant of error for Quality Indicator 1 because renal failure was required for eligibility.

A comparison of patient characteristics of gout patients subject to allopurinol medication error vs subjects without error for each of the validated quality indicators: mean (±s.d.) or number (%)

| . | Quality Indicator 1: Dosing in context of renal failure (n = 185) . | . | Quality Indicator 2: Dose adjustment with concomitant use of allopurinol and azathioprine/6-MP (n = 52) . | . | Quality Indicator 3: Treatment of asymptomatic hyperuricaemia (n = 471) . | . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Error (n = 48) . | No error (n = 137) . | Error (n = 13) . | No error (n = 39) . | Error (n = 267) . | No error (n = 204) . | |||

| Sociodemographic | |||||||||

| Age: yr (s.d.) | 70.6 (14.8) | 70.5 (12.6) | 56.0 (9.1) | 55.7 (14.1) | 60.7 (15.7) | 58.0 (16.7) | |||

| Male sex (%) | 36 (75%) | 86 (63%) | 11 (85%) | 29 (75%) | 203 (76%) | 143 (70%) | |||

| Comorbidity | |||||||||

| Coronary artery disease (%) | 31 (65%) | 86 (63%) | 5 (39%) | 18 (46%) | 78 (29%)* | 42 (21%) | |||

| Hypertension (%) | 19 (40%)* | 78 (57%) | 8 (62%) | 26 (67%) | 74 (28%)* | 82 (40%) | |||

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 4 (8%) | 16 (12%) | 3 (23%) | 7 (18%) | 25 (9%) | 15 (7%) | |||

| Renal failure† (%) | – | – | 3 (23%) | 19 (49%) | 24 (9%)* | 4 (2%) | |||

| Concomitant drug use | |||||||||

| Diuretics (%) | 36 (75%) | 97 (71%) | 9 (69%) | 27 (69%) | 84 (32%) | 75 (37%) | |||

| Cyclosporin or FK-506 (%) | 2 (4%) | 10 (7%) | 12 (92%) | 25 (64%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.5%) | |||

| Total medications (s.d.) | 3.4 (2.3) | 3.8 (2.8) | 4.8 (3.0) | 3.8 (3.0) | 2.9 (2.2)* | 1.8 (2.2) | |||

| Follow-up duration (yr) | – | – | – | – | 3.8 (2.6) | 3.7 (2.4) | |||

| . | Quality Indicator 1: Dosing in context of renal failure (n = 185) . | . | Quality Indicator 2: Dose adjustment with concomitant use of allopurinol and azathioprine/6-MP (n = 52) . | . | Quality Indicator 3: Treatment of asymptomatic hyperuricaemia (n = 471) . | . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Error (n = 48) . | No error (n = 137) . | Error (n = 13) . | No error (n = 39) . | Error (n = 267) . | No error (n = 204) . | |||

| Sociodemographic | |||||||||

| Age: yr (s.d.) | 70.6 (14.8) | 70.5 (12.6) | 56.0 (9.1) | 55.7 (14.1) | 60.7 (15.7) | 58.0 (16.7) | |||

| Male sex (%) | 36 (75%) | 86 (63%) | 11 (85%) | 29 (75%) | 203 (76%) | 143 (70%) | |||

| Comorbidity | |||||||||

| Coronary artery disease (%) | 31 (65%) | 86 (63%) | 5 (39%) | 18 (46%) | 78 (29%)* | 42 (21%) | |||

| Hypertension (%) | 19 (40%)* | 78 (57%) | 8 (62%) | 26 (67%) | 74 (28%)* | 82 (40%) | |||

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 4 (8%) | 16 (12%) | 3 (23%) | 7 (18%) | 25 (9%) | 15 (7%) | |||

| Renal failure† (%) | – | – | 3 (23%) | 19 (49%) | 24 (9%)* | 4 (2%) | |||

| Concomitant drug use | |||||||||

| Diuretics (%) | 36 (75%) | 97 (71%) | 9 (69%) | 27 (69%) | 84 (32%) | 75 (37%) | |||

| Cyclosporin or FK-506 (%) | 2 (4%) | 10 (7%) | 12 (92%) | 25 (64%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.5%) | |||

| Total medications (s.d.) | 3.4 (2.3) | 3.8 (2.8) | 4.8 (3.0) | 3.8 (3.0) | 2.9 (2.2)* | 1.8 (2.2) | |||

| Follow-up duration (yr) | – | – | – | – | 3.8 (2.6) | 3.7 (2.4) | |||

6-MP, 6-mercaptopurine.

*P< 0.05 for difference in patient factor; patients with prescribing error vs those without error within quality indicator.

†Renal failure included definite and probable cases; not examined as determinant of error for Quality Indicator 1 because renal failure was required for eligibility.

Rates of practice deviation from three validated quality indicators developed to assess quality of allopurinol use: results from the UK General Practice Research Database (GPRD). AZA, azathioprine.

Patient characteristics of those eligible for the analyses are summarized in Table 2. In age-adjusted analyses, male sex, total medications taken and chronic renal failure (definite or probable) were significantly associated with increased odds of receiving treatment for asymptomatic hyperuricaemia (Table 3). In contrast, both hypertension and diuretic use were associated with lower odds of receiving such treatment. These results were not changed after multivariable adjustment. Our results were also unchanged when we included only those with definite renal failure in the multivariable model (data not shown).

Association of patient factors with the treatment of asymptomatic hyperuricaemia (Quality Indicator 3) (n = 471)

| . | Age-adjusted . | . | Multivariable-adjusted . | . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient factor . | OR . | 95% CI . | OR . | 95% CI . | ||||

| Sociodemographic | ||||||||

| Age | – | – | 1.01 | 1.00–1.03 | ||||

| Male sex | 1.67 | 1.07–2.60 | 1.82 | 1.10–2.99 | ||||

| Comorbidity | ||||||||

| Coronary artery disease | 1.44 | 0.91–2.30 | 1.26 | 0.74–2.15 | ||||

| Hypertension | 0.54 | 0.37–0.80 | 0.58 | 0.38–0.88 | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.24 | 0.63–2.42 | 1.20 | 0.57–2.54 | ||||

| Chronic renal failure* | 4.55 | 1.54–13.41 | 4.89 | 1.58–15.11 | ||||

| Concomitant drug use | ||||||||

| Diuretics | 0.63 | 0.41–0.96 | 0.46 | 0.27–0.77 | ||||

| Cyclosporin or FK-506 | – | – | – | – | ||||

| Total medications | 1.17 | 1.07–1.28 | 1.25 | 1.12–1.40 | ||||

| Follow-up duration (yr) | 1.03 | 0.96–1.11 | 1.04 | 0.96–1.13 | ||||

| . | Age-adjusted . | . | Multivariable-adjusted . | . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient factor . | OR . | 95% CI . | OR . | 95% CI . | ||||

| Sociodemographic | ||||||||

| Age | – | – | 1.01 | 1.00–1.03 | ||||

| Male sex | 1.67 | 1.07–2.60 | 1.82 | 1.10–2.99 | ||||

| Comorbidity | ||||||||

| Coronary artery disease | 1.44 | 0.91–2.30 | 1.26 | 0.74–2.15 | ||||

| Hypertension | 0.54 | 0.37–0.80 | 0.58 | 0.38–0.88 | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.24 | 0.63–2.42 | 1.20 | 0.57–2.54 | ||||

| Chronic renal failure* | 4.55 | 1.54–13.41 | 4.89 | 1.58–15.11 | ||||

| Concomitant drug use | ||||||||

| Diuretics | 0.63 | 0.41–0.96 | 0.46 | 0.27–0.77 | ||||

| Cyclosporin or FK-506 | – | – | – | – | ||||

| Total medications | 1.17 | 1.07–1.28 | 1.25 | 1.12–1.40 | ||||

| Follow-up duration (yr) | 1.03 | 0.96–1.11 | 1.04 | 0.96–1.13 | ||||

*Definite or probable renal failure.

Association of patient factors with the treatment of asymptomatic hyperuricaemia (Quality Indicator 3) (n = 471)

| . | Age-adjusted . | . | Multivariable-adjusted . | . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient factor . | OR . | 95% CI . | OR . | 95% CI . | ||||

| Sociodemographic | ||||||||

| Age | – | – | 1.01 | 1.00–1.03 | ||||

| Male sex | 1.67 | 1.07–2.60 | 1.82 | 1.10–2.99 | ||||

| Comorbidity | ||||||||

| Coronary artery disease | 1.44 | 0.91–2.30 | 1.26 | 0.74–2.15 | ||||

| Hypertension | 0.54 | 0.37–0.80 | 0.58 | 0.38–0.88 | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.24 | 0.63–2.42 | 1.20 | 0.57–2.54 | ||||

| Chronic renal failure* | 4.55 | 1.54–13.41 | 4.89 | 1.58–15.11 | ||||

| Concomitant drug use | ||||||||

| Diuretics | 0.63 | 0.41–0.96 | 0.46 | 0.27–0.77 | ||||

| Cyclosporin or FK-506 | – | – | – | – | ||||

| Total medications | 1.17 | 1.07–1.28 | 1.25 | 1.12–1.40 | ||||

| Follow-up duration (yr) | 1.03 | 0.96–1.11 | 1.04 | 0.96–1.13 | ||||

| . | Age-adjusted . | . | Multivariable-adjusted . | . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient factor . | OR . | 95% CI . | OR . | 95% CI . | ||||

| Sociodemographic | ||||||||

| Age | – | – | 1.01 | 1.00–1.03 | ||||

| Male sex | 1.67 | 1.07–2.60 | 1.82 | 1.10–2.99 | ||||

| Comorbidity | ||||||||

| Coronary artery disease | 1.44 | 0.91–2.30 | 1.26 | 0.74–2.15 | ||||

| Hypertension | 0.54 | 0.37–0.80 | 0.58 | 0.38–0.88 | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.24 | 0.63–2.42 | 1.20 | 0.57–2.54 | ||||

| Chronic renal failure* | 4.55 | 1.54–13.41 | 4.89 | 1.58–15.11 | ||||

| Concomitant drug use | ||||||||

| Diuretics | 0.63 | 0.41–0.96 | 0.46 | 0.27–0.77 | ||||

| Cyclosporin or FK-506 | – | – | – | – | ||||

| Total medications | 1.17 | 1.07–1.28 | 1.25 | 1.12–1.40 | ||||

| Follow-up duration (yr) | 1.03 | 0.96–1.11 | 1.04 | 0.96–1.13 | ||||

*Definite or probable renal failure.

Discussion

In this large population-based study, we observed a number of medication-related errors with the use of allopurinol among patients in the UK followed by general practitioners. Approximately one-quarter to one-half of all patients eligible for the individual validated quality of care indicators appear to be subject to possible allopurinol prescribing error, suggesting that inappropriate prescribing practices may be widespread with the use of this agent. Older age, male sex, the presence of polypharmacy, and select disease comorbidity are strongly associated with inappropriate allopurinol prescribing for asymptomatic hyperuricaemia.

These results corroborate those of previous small, hospital-based investigations suggesting that allopurinol is often prescribed inappropriately. In separate audits of new allopurinol prescriptions, independent groups reported that the prescribed dose exceeded the recommended dose (based on renal function) in approximately half of patients [4, 5]. In another study, 22% of patients receiving a new prescription for allopurinol required a pharmacy-based intervention because of either excessive dosing or lack of an approved drug indication [3]. In another study, over half of patients who developed allopurinol-related hypersensitivity were reported to have been prescribed allopurinol for the treatment of asymptomatic hyperuricaemia [2], a practice without current evidence-based support. While there have been numerous case reports of inappropriate administration of allopurinol with concomitant 6-MP/azathioprine [13, 14] this is the first study to our knowledge to quantify the magnitude of this problem on a population level.

The reduced odds of allopurinol prescribing error in patients with hypertension or diuretic use was counter to our a priori hypothesis. These factors appeared to be protective in Quality Indicator 3 where they were associated with lower odds of receiving urate-lowering treatment for asymptomatic hyperuricaemia. Given the well-known association of both of these factors with elevations in serum urate [15–17], one possible explanation is that physicians are less apt to initiate therapy when there is a clear secondary cause for the laboratory abnormality in the absence of gouty arthritis.

It is noteworthy that patients with chronic renal failure were nearly five times more likely than those without renal failure to receive medical intervention for asymptomatic hyperuricaemia, which is problematic since renal impairment has been identified as a risk factor for the development of allopurinol hypersensitivity [2]. Given the inverse relation of renal function with serum urate levels [18], it is possible in our study that renal failure (in addition to older age and male sex) simply served as a surrogate for higher serum urate levels (values not available in this data set). This is relevant because physicians may have serum urate thresholds at which they opt to initiate urate-lowering therapy even in asymptomatic patients [19]. While there appears to be an association of hyperuricaemia with cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [20–25], there is not current evidence supporting a cardioprotective effect of allopurinol treatment in asymptomatic patients. It is possible that recommendations (and quality of care indicators) may change with our evolving understanding of hyperuricaemia and its potential role in vascular pathology.

Despite the strengths of our methodological approach and the large representative sample of the UK population, there are limitations to this study. Similar to other national investigations of gout from the UK [26, 27], we relied on physician diagnoses to define gout status, a definition that can be subject to misclassification. There was also the potential for misclassification of renal disease and asymptomatic hyperuricaemia, since we did not have access to actual laboratory values for serum creatinine and urate levels. We defined both using physician diagnostic codes and appropriate algorithms, which have been shown to identify health conditions that are recognized by the physician. Since our focus was on quality of care rendered for recognized diagnoses, diagnostic specificity was of less concern than the processes of care provided to the patients. In addition, our definition of the quality indicator eligibility was rigidly specified and, as a result, only a small minority of gout patients prescribed allopurinol was eligible for our analyses.

Because we used strict eligibility criteria, we probably excluded many patients who would have been otherwise eligible for the analysis. We identified only 471 patients with asymptomatic hyperuricaemia, representing only a small fraction of the GPRD database. In contrast, population-based studies suggest that 15–20% of the population has asymptomatic hyperuricaemia. However, because we used highly specific selection criteria designed to identify those most vulnerable to error, we anticipate that our results may underestimate the frequency of inappropriate allopurinol prescribing. Lastly, this study was limited to patients cared for by general practitioners in the UK and, therefore, the results may not be generalizable to other populations and/or physician groups. The lack of provider-level data is a limitation, since training level and experience could impact medication error.

In a recent survey of UK general practitioners, an overwhelming majority (86%) claimed to be confident in the diagnosis and management of gout [28]. Of interest, general practitioners were much less likely to express confidence in their management of other musculoskeletal conditions, including polymyalgia rheumatica (39%), early rheumatoid arthritis (17%) and osteoporosis (29%). Less than one-third routinely referred gout patients to a rheumatologist or other specialist. This compares to a rheumatology referral rate of over 85% for patients with early rheumatoid arthritis and 75% for polymyalgia rheumatica. Our results suggest that gout management among general physicians may merit further scrutiny. These findings also underscore the need for future interventions aimed at reducing inappropriate allopurinol use in gout and asymptomatic hyperuricaemia, particularly among older men, those with renal impairment, and those taking multiple concomitant medications.

This study was supported by a grant from AHRQ (U18-HS-10389). T.R.M. receives support from NIH/NIAMS (K23-AR0500004-01A1) and the Arthritis Foundation (National and Nebraska Chapters).

J.T.F. has received support from Cephalon, Pfizer and the Philadelphia Health Care Trust. K.G.S. and T.R.M. consultants to Tap Pharmaceuticals. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

Mikuls T, Farrar J, Bilker W, Fernandes S, Schumacher H Jr, Saag K. Gout epidemiology: results from the UK General Practice Research Database, 1990–1999.

Hande K, Noone R, Stone W. Severe allopurinol toxicity: description and guidelines for prevention in patients with renal insufficiency.

Devlin J, Bellamy N, Bayliff C. Observations and effects of educational consults on allopurinol prescribing.

Smith P, Karlson N, Nair B. Quality use of allopurinol in the elderly.

Stamp L, Gow P, Sharples K, Raill B. The optimal use of allopurinol: an audit of allopurinol use in South Auckland.

Mikuls T, MacLean CH, Olivieri J et al. Quality of care indicators for gout management.

Shekelle P, MacLean CH, Morton SC, Wenger NS. Assessing care of vulnerable elders: methods for developing quality indicators.

Garcia Rodriguez L, Perez Gutthann S. Use of the UK General Practice Research Database for pharmacoepidemiology.

Jick H, Jick S, Derby L. Validation of information recorded on general practitioner based computerised data resource in the United Kingdom.

Onder G, Landi F, Cesari M, Gambassi G, Carbonin P, Bernabei R. Investigators of the GIFA Study. Inappropriate medication use among hospitalized older adults in Italy: results from the Italian Group of Pharmacoepidemiology in the Elderly.

Mamun K, Lien CT, Goh-Tan CY, Ang WS. Polypharmacy and inappropriate medication use in Singapore nursing homes.

Kennedy D, Hayney M, Lake K. Azathioprine and allopurinol: the price of an avoidable drug interaction.

Venkat Raman G, Sharman V, Lee H. Azathioprine and allopurinol: a potentially dangerous combination.

Hochberg M, Thomas J, Thomas DJ, Mead L, Levine DM, Klag MJ. Racial differences in the incidence of gout: the role of hypertension.

Campion E, Glynn R, DeLabry L. Asymptomatic hyperuricemia. Risks and consequences in the Normative Aging Study.

Roubenoff R, Klag MJ, Mead LA, Liang KY, Seidler AJ, Hochberg MC. Incidence and risk factors for gout in white men.

Hahn P, Edwards L.

Stuart RA, Gow PJ, Bellamy N, Campbell J, Grigor R. A survey of current prescribing practices of antiinflammatory and urate-lowering drugs in gouty arthritis.

Woo J, Swaminathan R, Cockram C, Lau E, Chan A. Association between serum uric acid and some cardiovascular risk factors in a Chinese population.

Levine W, Dyer AR, Shekelle RB, Schoenberger JA, Stamler J. Serum uric acid and 11.5-year mortality of middle-aged women: findings of the Chicago Heart Association Detection Project in Industry.

Freedman D, Williamson DF, Gunter EW, Byers T. Relation of serum uric acid to mortality and ischemic heart disease. The NHANES I Epidemiologic Follow-up Study.

Bengtsson C, Lapidus L, Stendahl C, Waldenstrom J. Hyperuricemia and risk of cardiovascular disease and overall health. A 12-year follow-up of participants in the population study of women in Gothenburg, Sweden.

Abbott R, Brand FN, Kannel WB, Castelli WP. Gout and coronary heart disease: the Framingham Study.

Fang J. Alderman M. Serum uric acid and cardiovascular mortality: NHANES I epidemiologic follow-up study, 1971–1992.

Currie W. Prevalence and incidence of the diagnosis of gout in Great Britain.

Harris C, Lloyd C, Lewis J. The prevalence and prophylaxis of gout in England.

Author notes

1Department of Medicine, University of Nebraska Medical Center, 2Omaha VA Medical Center, Omaha, NE, 3Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics and Center for Education and Research in Therapeutics (CERT), University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, 4Department of Medicine and 5Center for Education and Research in Therapeutics (CERT) in Musculoskeletal Disorders, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, USA.

Comments